Poem Via Purgativa

I was constipated

the way a man is constipated

when he mistakes accumulation for worth.

Days of holding—

not food,

but judgments,

half-read arguments,

moral cautions sharpened into weapons

I never had the courage to use.

I told myself I was careful.

I was hoarding.

I told myself I was deep.

I was afraid of waste.

My mind became a colon of citations:

everything retained,

nothing digested,

ideas fossilized before they could nourish.

Even my virtues hardened—

ethics as impaction,

principle as obstruction.

I walked around like this for years

calling it scholarship,

calling it seriousness,

calling it faith.

Meanwhile the body kept score.

It always does.

It said: you cannot think your way

out of rot.

When it came, it was not catharsis.

No music.

No metaphor gentle enough to save me.

Just pain,

sweat,

the obscene knowledge

that what I had guarded

was shit.

And when it left me—

heavy, sour, undeniable—

I did not feel clean.

I felt exposed.

Because the relief revealed the lie:

I had believed retention was holiness,

that nothing passing through me

meant nothing could accuse me.

But what remains when nothing moves

is not purity.

It is decay with good posture.

I sit now in the aftermath,

emptier,

less impressive,

no longer armored by my own blockage.

My life is not fixed.

My mind is not redeemed.

My morals are still compromised—

but at least

they are moving again.

And maybe this is what repentance is:

not elevation,

not insight,

but the humiliating willingness

to let what is dead

leave you

before it poisons

everything else.

Nova : Nothing New

I.

The road south does not warn you. Eucalyptus, winter wheat, the ordinary grammar of arrival— then the field opens its throat.

Faces rise from soil like a congregation that forgot to leave, each portrait a midrash mounted on silence: Here stood breath. Here, rhythm. Here, the body before it learned its own fragility.

Kalaniyot gather at their feet, red anemones spreading the way blood does not spread— slowly, with intention, a second spring that knows its season has been renamed.

I cannot rush. Each step a trespass, each glance a debt unpaid.

This is not absence. This is over-presence— the place where tzimtzum failed, where God did not contract enough to let the human survive the density of what is real.

Music opened bodies here. Now silence does the same.

II.

מגרש הרכבים השרופים / קיר המכוניות

Near Moshav Tekuma

The vehicles remember.

Stacked metal, oxidized grief, each chassis a sentence stopped mid-syllable. Doors torn, frames perforated— the punctuation of bullets writing nothing anyone wanted to read. 1,560 in number-unfathomable assault.

Two black Toyotas sit unburned, gun turrets welded to their backs, placed in the circle like an answer no one asked for.

My physician's eye catalogues: heat deformation, blast pattern, penetration depth. But something older intrudes— something that does not measure.

In the Talmud, stones cry out when blood is spilled. Here, steel learns to weep.

A white pickup from Nir Oz stands apart, doors flung wide, as though the driver might return, as though leaving were still possible.

III.

At Be'eri, the homes do not explain themselves. They are already fed up with gapers

Only peeking from the road allowed.

No front line was drawn here. The front came through the kitchen, through the children's room, through the ordinary architecture of morning.

What do you call a threshold that no longer divides? What bracha for a doorway that held nothing back?

The mezuzah may still hang— I did not look. Some things should not be checked.

IV.

In Sderot, the murals try. Painted flags, blue sky, the grammar of endurance. But bullet holes interrupt the art, the real puncturing representation as it always does.

A mirage police station stands between order and exhaustion, vigilance and the slow fatigue of being the margin that never moves inward.

No triumph here. Only the repetition of getting up.

V.

I came looking for nothing. I found obligation.

The God who survives this place is not the God of rescue, not the Shomer Yisrael who guards with outstretched arm. That God did not show.

What remained was the other Presence— the one who stays without fixing, who witnesses without redeeming too quickly, who sits shiva in the ash long after the comforters have left.

The vav is broken here. וְהוּא—and He— cracked at the center, the letter that joins learning what it means to hold two fragments that will not fuse.

VI.

Do not rush toward meaning. Sacrifice, heroism, rebirth— the old words circle like relatives who do not know what to say.

This ground will not be narrated. It demands a slower faith: unresolved grief, moral ambiguity, the scandal of survival that offers no absolution to the one who walked away.

VII.

The road north bends gently. The sky remains indifferent. I carry nothing I can name.

Only this:

The earth, burned and planted, danced upon and violated, has written something on the body.

It will take years to read. It may take longer to refuse the false translations.

For now, I do not interpret. I only remain a little less whole, a little more present, a fractured letter in a sentence still being written.

For the faces in the field, for the steel that remembered, for the doors that did not hold.

The Yechida as Higher Power

They told me to look up—

to surrender to something greater,

external, transcendent,

the God of ladders and heavens,

of confession aimed skyward.

But when I prayed—truly prayed,

not the rote mechanics of petition

but the wordless reaching

that begins when language fails—

I found no upward.

Only inward.

Only down,

beneath the chattering nefesh,

past the storming ruach,

deeper than neshama’s knowing,

to the place where asking stops

because the asker dissolves.

יחידה

The singular one.

Not a power above me

but the innermost point—

the spark that was never not divine,

the knot the mystics say

was tied before separation

and never untied.

They spoke of absolutes—

honesty, purity, unselfishness, love.

Noble ascents.

But the yechida knows no ascent;

it was never elsewhere.

At the limit,

when all structures thin,

I did not find rescue waiting

like an answer descending from above.

I found the veils worn transparent,

the light already present

finally able to appear.

Not salvation from outside

but recognition from within.

They ask: Who do you pray to?

And I cannot say Ein Sof,

cannot rehearse the metaphysics of tzimtzum,

the dialectic of yesh and ayin

that fills essays with footnotes

and quenches no thirst.

I pray to the self that is not a self.

To the watcher behind the watcher.

To what remains

when identities exhaust themselves

and something still breathes.

Call it yechida.

Call it chelek Eloka mi-ma’al mamash—

a literal portion of God above.

Call it the still, small voice

that sounds like thought

yet knows what was never learned.

Maps describe movement outward—

belief, surrender, confession, repair, seeking.

Necessary paths.

But my movement spirals inward:

strip, descend, loosen, dissolve—

until even the one who descends

is forgotten

and only ground remains,

wearing a human face.

This is not inflation,

the ego masquerading as holiness.

This is annihilation—

the recognition that what falls away

was never the Self to begin with.

Bittul—

self-nullification,

the Hasidic art of stepping aside.

Not submission to an alien God

but dissolution of the alien self,

the one assembled from fear and grasping,

the one that required masks

to feel real.

When that one loosens—

again and again,

in prayer, in silence,

in the refusal to cling—

what remains is not absence.

What remains is yechida:

the self that was divine all along,

hidden beneath garments,

waiting to be recognized.

So when they say higher power

I hear deeper power.

When they say outside

I hear inside-out.

When they say surrender

I hear return.

The topology inverts,

yet the practice holds.

And in unlikely places

people rediscover

what mystics always knew:

that the God we seek

has been seeking us

from within.

Not higher.

Deeper.

Not outside.

Inside-out.

Not surrender to another.

Return to Self.

I practice recognizing

what was never lost,

clearing the debris

from a sanctuary

that was always holy.

Not becoming spiritual.

Uncovering what is.

Not finding God.

Allowing God

to find itself

in this vessel

that somehow still

carries fire.

Art by David Friedman

Kaballah of October 7th

The vacated space of the Chalal hapanui… חלל הפנוי

Where bechirah runs amock

Radical freedom’s dark side

Bears down heavily-

The price of existence outside Him

The imperfection of finitude

We, who bear His gevurot

Creation as catastrophe

The very weight of the (apparent) tzimtzum , surely כפשוטו.

We suffer the atrocities..

Worse, powerless as onlookers,

I now understand the millions of fellow Jews watch

The unfolding Shoah, with more compassion than ever

For their sense of impotence.

Knowing that beyond reward and punishment

And all the tired theodicies

Good and evil,

victim and perpetrator,

Lies this hidden intuitive sense

That Being, Mind, and the order of things

Has made space within Himself for all the horror

Of all history, the failed experiment of creation and

its human nadir.

That for his Chessed to thrive

The DIN must be vomited, expelled, demonized,

And expressed in the murderous acts of the enemy to this day.

However comes along the adept,

The shaman who has already surrendered

Knowing the murderous enemy lies within

That somehow he, as onlooker, is complicit

For accepting reality as somehow good.

When Dinur testified at the Eichmann trial

His apoplexy forcing him to confront the possibility

That inside each of us -given the right conditions- we too

Could exhibit the same murderous impulses, if banal-

What might he say looking into the Gazan tunnels?

Peering into that deep darkness

Might he see the same barbarous acts in himself?

What might I say in my ever ambivalence,

“horrific but understandable”?

Not excusing their behavior for a second,

Not even parsing the implacable conflict since 1948

Nor the self-righteous thuggery of the settlers

On the contrary

Holding the past etched in memory

(The Kabbalah of the crematoria

The holiness of the smoke rising of plumes of white bone-ash

And all ensuing genocides since)

Inspired by the technology of killing

The doubting Thomas looks into the Gazan tunnels

To a new era of psychic terrorism.

Out there

and the horror of accepting this occurring holographically within.

When will this be enough?

Is that the definition of geulah?

When the divine is finally exhausted, emptied of its non-divine

Watching all this from its Elysian heights?

She is a jealous mistress

Schechinah remains in the rising smoke, the charred victims,

And now in the bloodied hands of the drugged murderers

She wear black in the tunnels, out of sight,

(like in Reb Chaim Vital’s dream the Kotel circa 1777)

And in my own darkness, the Princess is lost

and beyond resuscitation by the zaddik

Beyond rescue in the depths of despair.

Yet it is in the darkest of hours

In the deepest tunnel

In the hopeless heart

That the only attitude, the possible response must be

Further surrender

deeper silence

a screaming Nachman-type silence

a bitul to the reality as it is

beyond pain

beyond atrocity

echoing the Piacezna in his deepest despair (Eish Kodesh)

a descent of such depths that even screaming איה מקום כבודו

will not propel one to כתר

it is a fall into the חלל הפנוי

that vacated space of acceptance

that this is all His רצון

Before He Thought Silence

Before He thought, about this world An idea arose in His mind, Israel.

In the silence of shtok kach ala bemachshava

He thought of the martyrs, Rabbi Akiva, and the mothers who would sacrifice their children in the churches of Mainz, Speyer and Worms, and the babies who would go up in the flames of Hitler’s inferno.

In that first breath of life He too had to die a bit.

In His plenitude, in His pleroma He too had to make room, of Not-Him, an internal dying to the self.

From His breath, I breathe... That unconscious deep inhalatory gasp recognized only when I surface after being too long submerged

In the purifying waters of the supernal mikveh,

When I realize just how primitive this reflex gasp is,

Unable to control it. (And they say water boarding is not torture!)

But in that breath-His exhalation into my lungs comes at a price

For He demands, requests, begs, We live, and return the favor!

But how! We finite creatures living out our puny lives

At the end of which we too must "give up the ghost"

And breathe that last breath

When that very last exhalation gets no inspiration and We stop....breathing

We ex-pire.

Yet taught in the secrets of Torah about the "kiss of death" reserved for the precious few, the Patriarchs, Moses, the Tzaddik/saints and Reb 'Melech', (even my wife's grandfather! was witnessed)-in whose death mirrored that primordial act of creation- in the kiss-

the breath is literally sucked out, sucked back into the divine. misas neshikah

But those chosen received this gift precisely because they lived each moment, Each breath as if...what was being asked,

What was being demanded,

Was a readiness at any moment,

For mesiras nefesh

To give infinite pleasure back to the divine By self-sacrifice

To give up the ghost immediately upon request.

As the martyrs were so ready- the daily rituals and customs seem to focus on training us for the possibility for such similar demands at focal points in history- (do we need to rehearse them again?)

The martyrs argue among themselves as to who should go first,

Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel or Rabbi Shimon the High Priest,[1]

Who should be first to die, and As the Piacezna mourns his son in the fall of 1939, in the Ghetto Warsaw,

He rereads the death of Sarah our matriarch[2]

As one of possible suicide in order to confront her Maker With the real question behind the Akeda, the binding of Isaac.

Not his survival rather his descendants' martyrdom! She foresaw in her prophetic mind Generation after generation of blood, and man's inhumanity to man.

This was not the blessing promised to her husband! She was to present herself prematurely to protest and complain

That this might be the lot of her descendants. "And the remaining of her years did not protest."

But God demands no less of what He himself gave in creating this world.

Mesiras nefesh as imitato dei, A true replication of creation, in the very act of dying.

By dying and giving Him our last breath

We, too, act in creation in the very surrender to creation.

We, too, breathe back into God what He had given so painfully

By limiting Himself in this world.

By transforming our desire for self-preservation Into the desire to breathe back into Him

We are replicating His desire to create

Resulting in His dying-if only a little.

When the angels then protest citing "zu Torah vezu schora!" Is this Torah and is this its reward" God's response remains "shtok! Kach ala bemachshava.

“Be silent! For thus it arose in My mind".

[1] Avot deRabbi Natan 38:3. the reason being "not to watch the death of my friend" but reworked in Eish Kodesh By R. Kalonymous Kalman Schapiro Succos 5702 as "I want to be t'chila the first to be martyred because being first forges new paths in worship. Alluding to the death of his beloved son; who also was meant to forge new paths in hassidut."

[2] See Rashi to Gen. 23:1-2. and midrashim op cit.

The Latest Station In a Long Mythical Drama

If creation was the expulsion of DINIM

From within the pleroma of the infinite

An infinite desire to rid itself of itself,

Of its GEVUROT, once and for all,

Then the world as is, the cosmos, ourselves

Represent this divine refuse

(remember Jung’s first dream, a turd falls from sky onto his father’s altar!)

Then its culmination, terminus ad quo, its nadir

When time, space and people coalesced all at once

(the reverse of the High Priest in the holiest place at the Holiest time

Pronouncing the Ineffable Name)

Which allowed for the supreme manifestation of

GEVUROT/DINIM/the demonic

To come to a crashing climax

When history stopped being history

And the divine expulsion of Lucifer was complete

In the ovens of Auschwitz.

For surely,

As Kabbalah teaches,

The very mystery of the universe

The single claim above all others

Is that “what s below is mirrored above” and vice versa

This mirroring of the divine,

The verisimilitude,

Manifests both its good and dark side (kelippa/sitra achra)

And in this paradoxical unity of upper and lower worlds

(Where Rabbi Akiva warns his students embarking on a trip to

the upper worlds

“do not split between the upper and lower waters!”)

The illusion of reality, the world, history and time

Must be pierced by the visionary adept,

As part of his worship,

Who must see beyond geography, even the laws of physics

and the needs of self,

And suffer the evil from the above

Since he “knows” the divine disconnected self (Schechina)

is suffering down here too.

He is a knight of the Matronita. The Lost Princess

And where She goes he follows

In Her suffering

He too feels the pain and longs for her reunification with Her consort.

For the exile of the human spirit below

Is mirrored above in an infinite fractured divine,

And this infinite divine pain is felt below

So the bloodletting and burst of genocidal fury

Against the chosen people

In the most refined kultur of Beethoven and Goethe,

Must be seen as an unleashing of a demonic force

That defies sociopolitical and historical analysis

Leaving a gap of understanding after all the historical facts

have been rationally analyzed and hypothesized.

This gap expressed only as the demonic,

Reflecting rather a Divine self-wounding of infinite proportion.

Resisting ideologies of theodicy and theoria that might justify, explain,

rationalize or even accept guilt (a very Rabbinic trope),

Resisting doctrines of good/evil, reward/punishment, vicarious suffering of

the righteous servant etc etc,

(Which held the faithful for a millennia

Who until hitherto were

Accepting of responsibility for each pogrom

Encoded in the liturgy, piyyutim and chronicles,

But no longer of use)

In the face of a million babies in the smoke filled chimneys

Of the crematoria.

So where to turn to?

In the infinite silence of the transcendent?

To make any sense of it, (forget Hester Panim)

Or jettison all theologies and theodicies once and for all?

The Kabbalist turns to midrashic and zoharic tropes

Of the feminine divine- Schechina,

Weeping as she left the Temple court, Jerusalem circa 70CE

The weeping city alone,

Or the hypostatic Rachel crying from her tomb in Bethlehem.

Watching her children chained into exile.

He turns to that Schechina, lost and disconnected from Her consort

Trapped down here in a world of demons/kelippot

Unable to reunite or bring the Messiah,

The weeping black widow by the Kotel,

And sits on the ground weeping on her behalf reciting Tikkun Rachel and

Leah at midnight.

In these tears he inhabits a new silent landscape, the wasteland.

In a black and white movie where all is grey,

He no longer sees his suffering in theological categories

Having spent centuries following the Lurianic kavvanot, tikkunim and zivugim,

Rituals and ascetic practices designed to get noticed upstairs,

To fix things upstairs,

Rolling in the snow, Tikkunei shelleg-mortifications and fasting.

He must now find a new path in a genocidal era

With no hope for deus ex machina

Or Messianic figure,

(for if Elijah should arrive now-he would turn him away

Having ignored the screams of a million babies and their mothers)

No, he returns to the paradigms of protest and pathos

Of the parables of a king weeping in his inner chamber

Lamenting the loss of his people

Unable to be consoled

And finds deep compassion within

Despite a resentment the size of Munich

And a gaping wound in the heart as deep as Hades.

For, as the hassidic masters claimed

The only path now is one of mittuk hadin,

The holographic Din within him, the demonic side of him,

By comforting the Lost Princess as she lies swooned in the Water Castle

And feeling her pain as she sees the infinite loss

(Like the night Reb Zisha awoke to the screams of a million babies

Running away from that little shtetl Ushpetzin

200 years before they fired up the ovens).

Or carry the weight of the Divine בכי

Like the Piacetzna instructed us before his deportation to Treblinka

To not focus on one’s own pain,

Rather be a merkava for Her pain

As She dies alongside the victims

An infinite weight to bear.

From that first tzimtzum of infinite contraction

A sea of infinite pain produced by this huge self-inflicted

Intra-divine vacuum/wound,

Down to the long history of man’s inhumanity to man,

Culminating in the horrors of the “years of Fury”,

And the current technology of the killing fields.

The adept collapses all time into the mirror of his own soul

Seeing across the infinity of space

With his third eye,

Seeing this demonic dark side of the divine

In himself too,

And realizing he alone can hold this paradox.

All he can utter

Despite this travesty

Is

יתגדל ויתקדש שמי רבא

Magnified and Sanctified be Thy Holy Name

We are born into this world

We die in this world

The Holy Name was there before us

The Holy Name remains after we are no longer here

We are forced to focus on the eternal Thou

Not our mortal selves

Not even our beloved losses

We focus on the mystery behind the Holy Name

The unfathomable grief and tragedy of life

And death all subsumed in the mystery of the Holy Name.

And develop compassion for His infinite, eternal pain.

This was never about us

Our biography

Neither our narrative

Nor our ending

We are merely the latest station in a long historical/mythical journey

Who tragically, were witness to

Or survivors of,

The culmination of a series of down-chaining

demonic forces that landed on our timeline

And in our backyard,

Of pure Wotan will, force, desire and bloodletting,

Unleashing a new age of genocidal fury.

What can he do

This adept?

But weep..,

And carry this dark side of the divine.

Gustav Klimt

Epigenetic Survival

“Vienna, that scrollworked bastion, smoldered with more demons of the future than the most forward-minded cities of the West.”

Frederick Morton, A Nervous Splendor

I dream of Dad last night

Looking at the roundness of a buttock

Approvingly…

In Vienna, female human anatomy and its proportions were taken oh so

seriously!

Reminding me of his father, who annually had to meet the Viennese store

buyer, enormous purchasing power

To sell his woolen goods for the next season,

She “demanding” he pinch her bottom with a Viennese wink.

His knowing look then glances at me!

Teaching me unconsciously the need for “good stock”

Implying a generous rump

In choosing the mother of the next alpha males….

The survival of the fitter, over centuries

The natural selection of choice partners

Requires the ample rump, stocked with fatty nutrients

To feed the sampling trees, the little ones especially during times of hunger,

And exile.

And that dream glance, the look, at me, transmitting this tool to the son.

Why would Dad come to me ?

And why with such base desire?

No high fallootin’ philosophical wisdom from beyond?

An insight? A thought? A piece of advice in my ongoing struggles?

Oh the Viennese double standards !!

How we choose our spouses!

What unconscious embedded predetermined desires…

Handed down in genetic formation

Tiny microscopic armies of DNA

Without a spoken word

Nor rhyme nor reason

He preferred the exotic slim Sephardi Indian beauty

Her delicate long fingers encompassing the neck of the fiddle, with mastery

Her playing seducing him for life

Forever devoted to this musical impressario

To what he sarcastically called the “cholent girls” from East London

Mostly from middle Europe themselves.

The body encodes these prejudices deep within the mitochondria

Not even permitting awareness to the person all the while,

making lifetime decisions about soul mates.

And Dad worshipped her until her dying breath

And beyond, forlorn, “my late wife” he would pine…

Thank you for the dream

With Every Breath על כל נשימה ונשימה

When a person is sleeping, however, the soul [neshama] [is left within him,and it] warms the body so it will not get too cold and die. That is what iswritten: “The spirit [neshama] of man is the lamp of the Lord” (Proverbs 20:27).

Rabbi Bisni, Rabbi Aḥa, and Rabbi Yoḥanan say in the name of Rabbi Meir: The neshama fills the entire body, and when a person sleeps, it ascends upward and draws life for him from above. Rabbi Levi said in the name of Rabbi Ḥanina: For each and every breath that a person takes, he must laud the Creator. What is the source? “Let every soul [neshama] praise God” (Psalms 150:6) – [read instead:] Let every breath [neshima] praise God.

Gen Rabba 14:9

A Hasidic master known as the holy Berdichever, the Kedushat Levi

He starts from Kol Haneshama tehalel yah. Levi Yitzhak asks us to recognize that every day we are a new creation. The Psalmist says, "Kol haneshama tehallel Yah" -- "Every living thing praises God" (Psalms 150:6). And the Midrash makes a tiny twist, yielding "Kol haneshima"-- "With every breath one praises God." Al kol neshima v’neshima – as the breath is constantly trying to leave us (release). But God keeps returning it to us. When this happens, we’re a great being. When this happens we have a great connection/joy/gratitude in serving God.

God breathes new life into us at each moment. Were it not for the loving vitality of the Divine, we would not survive from moment to moment. Each breath, each moment of life, is a new blessing, a new creation. And if we consider this, then we see that each moment is a new opportunity, a new beginning, in fact, a new lifetime. Entering each moment in this way, we may see clearly what is ours to do: to deepen love, to heal a soul, to save a life, to make a difference, to change the world.

Rabbi Levi Yitzchak of Berditchev (1740–1809)

Jastrow

The Inner Spark - The inner essence of the soul, which reflects, which lives, the true spiritual life, must have absolute, inner freedom. It experiences its freedom, which is life, through its originality in thought, which is its inner spark that can be fanned to a flame through study and concentration. But the inner spark is the basis of imagination and thought. If the autonomous spark should not be given scope to express itself, then whatever may be acquired from the outside will be of no avail.

This spark must be guarded in its purity, and the thought expressing the inner self, in its profound truth, its greatness and majesty, must be aroused. This holy spark must not be quenched through any study or probing. The uniqueness of the inner soul, in its own authenticity – this is the highest expression of the Divine light, the light planted for the righteous, from which will bud and blossom the fruit of the tree of life.

Orot Hakodesh 1:177

Rabbah said: If the righteous wanted, they could create a world. What

interferes? Your sins, as it is written (Isaiah 59:2), "Only your sins separatebetween you and your God." Therefore, if not for your sins, there would not be any differentiation between you and Him.

We thus see that Rabba created a man and sent it to Rav Zeira. He spoke to it, but it would not reply. But if not for your sins, it would also have been able to reply. And from what would it have replied? From its soul. Does a man then have a soul to place in it? Yes, as it is written (Genesis 2:7), "And He blew in his nostrils a soul of life." If not for your sins, man would therefore have a "soul of life." [Because of your sins, however] the soul is not pure.

This is the difference between you and Him. It is thus written (Psalm 8:6), "And You have made him a little less than God." What is the meaning of "a little"?

This is because [man] sins, while the Blessed Holy One does not. Blessed be He and blessed be His Name for ever and ever, He has no sins.

Sefer HaBahir 196

A Midrash to Neshama

Neshima…breath

With every breath

It dawns upon me

No longer the brainstem controlling the ebb and flow of air

But a gift from

Above

No longer a historical event

Now a moment by moment gift

Of life of breath

I breath out

My resentments fears anxieties

My harms, the wreckage of the past, the people I hurt

My acts of commission and omission

All goes out with the polluted exhalation

And then a moment of death until You revive me once again

With that primordial breath of life even against my will

I cannot even control that!

As if to say

“live despite”

Your flaws, your excesses, your selfishness, your use of other for your own

pleasure….despite despite despite!

Here it is another breath

Here it is I’m not ready for you

Another opportunity to surrender your self

Standing in the way of this hunger for real life, the source of life

Don’t settle for less

This breath is an invitation

To surrender more and drown in the divine

With a song

Just sit quietly

And drown

In the sorrow of what is right now warts ‘n all

This failed life breath out!

This “piss-poor protoplasm”. Breathe out!

This nutty perfectionism breathe out!

This insane worry about reputation it’s too late!

Now…wait…until you cannot hold it any longer

And you must surrender to the inhalation

See?

Let Him fill you up

Breathing in His divine flow

The “shefa” for the moment

The neshima עַל כּלָ נשְׁיִמהָ וּנשְׁיִמהָ

So…

Every morning

Upon awakening from the 60th of death…sleep

Your first inhalation should follow this awareness

You have been revived from the dead

But you are expected to die to life nonetheless

Through surrendering this day

A deep breath of life

Hold it in for as long as you can

And be grateful

That is your neshama!!!!

Radical Acceptance

Yesterday the horizon was razor sharp

The azure blue sky abruptly ending

Where the ocean claimed its watery turf

As if, heaven and earth’s boundaries

Were clearly delineated,

Their limits forever set

The divine …safely distanced from the mortal

The depths of the oceans, however, are another matter

The vast geological variations hidden below the calm surface

Betraying mountains as tall as and caverns as deep as

Anything on the surface.

What a contrast to the blue celestial nothingness of infinity.

Today however all is different

In the fog and haze of the same vista

The horizon is barely visible.

The grey clouds merge imperceptibly

into the ashen gray ocean

Everything lacks clarity as if…

The heavens touch earth only in such times of visual blurring

Of doubt and uncertainty

The horizon now representing a leakage of sorts

Allowing only now, for the perception of contact.

In these two visions of the horizon lies

the charge for radical acceptance

The blessings of clarity and acuity

But also the place where all is lost

All hope of contact is surrendered

All belief questioned

Especially of the lost Self

The illusions of control of one’s life

Even morality/religiosity

Teaching one the bloated sense of

imitation piety meant nothing,

Where the celestial spheres appear indifferent

to the suffering and anguish below

Where even the hiddenness of the Divine is itself hidden [1]

Yet the knowledge that another day will harbor

a different landscape and fuel

another vision of that same horizon

With the hope of divine intervention in all its clarity

forces on me

Bears down on me a radical acceptance.

That all this was meant to be this way

This duality

This oscillation

Hovering between the hope and despair

Clarity and confusion

Light and darkness

Pencil razor-sharp horizon yesterday

and blurring hues of grayness today

Learning so late in life

That equanimity of the soul is so precious

That deep connection with higher Self

Demands the light AND the darkness within

And accepting this is the very challenge.

[1] Likutei Moharan 56:3:19

Rami Shapiro

Dveykus, A New Definition

When totally broken

When there is nothing to support self

The breaking the disintegration the utter failure.

Of all mechanisms to relieve the deep anguish

Of facing the self in collapse

In free fall with no “rock bottom” to even break it

The only option is surrender.

Of even the modicum of achievements

Accepting the failure of this life

The list of defects, unsurmountable

The harms done to others, incalculable.

The belief that restoration is possible, shattered.

Dragged down to one’s knees.

Giving in, giving up, surrender to its limit.

Drowning in the tears of self-loathing

Even this needs to be sacrificed.

Maybe this is a new definition of Dveykus.

Forget the pious definitions !

Maybe just maybe …

The only way to connect with this perfect higher power.

Is one of emptying the self.

The very removal of the bloated importance of the grieving self

The tragic the inevitable the total suffering package

Free falling into what was feared as oblivion.

The loss of identity

The loss of all that was struggled for.

The loss of all that mattered and loved.

In this very fall

Is the total surrender into?

Dveykus

Dad's Tombstone Setting And Siyum

You will notice on the cover of your booklet over the picture of Sabba Willy the words:

And well may you ask why it is placed there and its connection with Sabba Uncle Willy?

My beloved father has been gone from this world some 10 months ago but it feels like a dream. The pictures videos and plethora of images you will see tonight give us the false impression of his ongoing aliveness and only exacerbate the pain of his loss.

Eugene’s evocative words on the tombstone, paralleling Mum’s in brevity yet capturing in a few lines the essence of Dad was mirrored by his remarks tonight.

Thanks to all our wonderful speakers including the Siyum and divrei brochoh from Motty, The Dvar Torah from Reb Refoel Moshe, the poetic lines from Chaim, the superb analysis of Dad by Batya, The poignant message from Vienna from cousin Anthony and above all the presence and blessings from Uncle Eric’s viola in response to all of us chanting:

“when I grow up I want to be like Uncle Eric” in unison!

Indeed the biggest tribute to dad was you! All of you! Showing up tonight to honor his memory.

Each of the four tables representing the four branches that emanated from his vision, each so different in temperament character, approach to life and Torah, yet each emanating from the tapestry of dad’s personality and he would have approved of each one you tonight with love humor sarcasm and wit.

My hope is we stay together as a family unified in our love of Mum and Dad and in their unconditional love of each and every one of us, that their memory guide us when we meet the hard spots in life and their inspiration of “just get on with it” as expressed here by uncles Eric’s message:

Let me return to the original question:

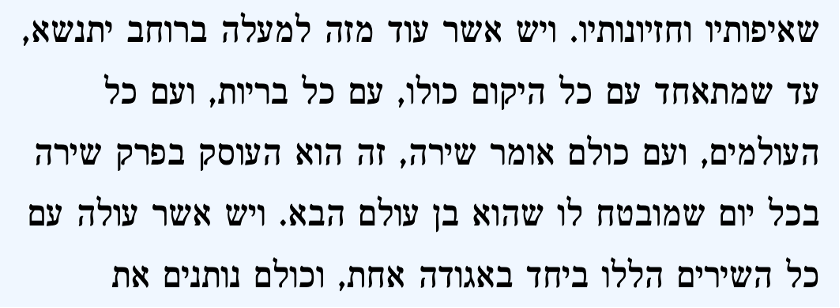

Its first mention of the term seems to come from a midrash (sorry Dad!) on the very first verse of the Song of Songs:

The song of songs which is Shlomo’s. Our Rabbis taught, “Every Shlomo (because they were at a loss to explain why [Scripture] did not mention his father, as it did in Mishlei and Koheles) mentioned in Shir Hashirim is sacred [=refers to God], the King to Whom peace שָׁלוֹם belongs.

Maseches Shavuos 35b.

It is a song which transcends above all other songs, which was recited to the Holy One, Blessed Is He, by His assembly and His people, the congregation of Yisroel.

Sabba too was a man of peace. In shul at work in the family he was a peacemaker. As I watched him rise in the ranks of the Federation to become a Vice President it was this precise quality that made him appreciated by all. In his lay-chairmanship of the Federation Kashrus he commanded the respect of both the United Synagogue Beth Din as well as the Kedassia sister supervising bodies thereby giving credibility to this fledgling authority to the point that EL AL acquired the Federation kashrus for all their flights out of Heathrow. His respect for the Dayanim on issues of kashrus as well as his ability to interact with secular officials of the airline proved to be the winning combination.

In the tense standoffs in shul during the High Holidays it was sabba the peacemaker who smoothed over hurt feelings.

My second citation comes from our liturgy :

Every Friday night we welcome the angelic guests to the Shabbes table with the yehi ratson that also contains the following phrase:

And we too pray for peace….Oh Almighty King who peace is His, bless me with peace ….

Sabba was a happy man always optimistic and as Eliyahu recorded…always saw the cup half full. God blessed him with inner peace despite the world at war despite Hitler…despite his losses and near death experiences…always looked on the bright side of life ( BTW he hated Monty Python! always favouring the sardonic European sense of humor).

In the last reference I remember weekly when

Dayan Braceiner and later Rabbi Zvi Telzner had the custom to invite a layperson the honor to begin the pizmon for seuda shlishit and Dad always was honored with the following zemirah:

He would then proceed to sing it a la German oberland tune….he must have remembered from Vienna…

May the Possessor of peace grant us blessing and peace—from left (north) and from right (south), peace upon Israel. The merciful One, He will bless His people with peace, and they will merit to see children and grandchildren occupying themselves with Torah and with commandments, [bringing] peace upon Israel. Advisor, Mighty God, Eternal Father, Prince of peace (Isaiah 9:5).

His own spirituality was always one of humility…he hated show and imitation piety…

In researching the term the most poignant Torah that encapsulated Sabba Willy’s sense of shalom I turn (as always) to the deepest writings of

Rav kook in Orot Hakodesh.

There is one who sings the song of his own life, and in himself he finds everything, his full spiritual satisfaction.

There is another who sings the song of his people. He leaves the circle of his own individual self, because he finds it without sufficient breadth, without an idealistic basis. He aspires towards the heights, and he attaches himself with a gentle love to the whole community of Israel. Together with her he sings her song. He feels grieved in her afflictions and delights in her hopes. He contemplates noble and pure thoughts about her past and her future, and probes with love and wisdom her inner spiritual essence.

There is another who reaches toward more distant realms, and he goes beyond the boundary of Israel to sing the song of humanity. His spirit extends to the wider vistas of the majesty of humanity generally, its noble essence. He aspires toward humanity's general goal and looks forward toward its higher perfection. From this source of life he draws the subjects of his meditation and study, his aspirations and his visions.

Then there is one who rises toward wider horizons, until he links himself with all existence, with all God’s creatures, with all worlds, and he sings his song with all of them. It is of one such as this that tradition has said that whoever sings a portion of the song each day is assured of having a share in the world to come.

And then there is one who rises with all these songs in one ensemble, and they all join their voices. Together they sing their songs with beauty, each one lends vitality and life to the other. They are sounds of joy and gladness, sounds of jubilation and celebration, sounds of ecstasy and holiness.

The song of the self, the song of the people, the song of humanity, the song of the world all merge in him at all times, in every hour. And this full comprehensiveness rises to become the song of holiness, the song of God, the song of Israel, in its full strength and beauty, in it full authenticity and greatness.

The name “Israel” stand for shir el, the song of God.

It is the Song of Songs of Solomon, shlomo, which means peace or wholeness. It is the song of the King whom is wholeness.

Rav Kook, "Lights of Holiness", trans. by Ben Zion Bokser (New York: Paulist Press, 1978)

Dad sung his own tune…was merutze…lakol…beloved by all…

He arose beyond all the pettiness to see the bigger whole…

Blown by the winds of war and fate to foreign lands…powerless and at the mercy of others…nonetheless he survived to build anew a family a legacy that reflected his deepest spirit… that of peace.

Dad was a happy man..

She-hashalom shelo...

His peace was his…

He embodied peace…

May his memory be an inspiration to his children and yotzei chalotzov

And his example of peace to klal yisroel.

Nature As A Sacred Text

I go down to the shore in the morning and depending on the hour the waves are rolling in or moving out, and I say, oh, I am miserable, what shallwhat should I do? And the sea says in its lovely voice: Excuse me, I have work to do.

Mary Oliver, A Thousand Mornings, p. 1

© 2012 by NW Orchard, LLC

First published by Penguin Press 2012

Running away

5 hours north

My buddies and I

Finally reach this carpet of beauty

standing transfixed by nature’s luxurious annual gift

These fall colors.

I go down to the shore in the morning

and depending on the hour the waves

are rolling in or moving out,

and I say, oh, I am miserable,

what should I do? And the sea says

in its lovely voice:

Excuse me, I have work to do.

seduce my eyes.

I’m drowning in jouissance.

The presence of the lake this morning ,calm

The glassy mirrored surface reflecting the regimental

yellow trees of the shoreline.

The lake, the trees

The water exclaims!

“Be quiet there’s work to be done.”

Bestowing their grace and rewarding the reverance

With my flowing heart…

There is a silence in the forest that is quieter than silence,

A stillness in the moist foliage under my boots.

The smell of the moist leaves is a unique scent.

That calms the memory from its wounds.

After the morning of mist and cloud , the sun

bursts forth through a thick grey cloud cover.

Shining a new light on the shimmering leaves

Gracing us above the forest line

There is a slight breeze making the perfection of the day complete.

In the red painted cabin in the woods

The wood-burning fire warms my chilly hands.

But the smoke makes me dizzy.

Also euphoric

Suddenly I awaken to the precious moment.

And gratitude for everything

Accepting finally the reality as is

The world as is.

Without ideology

Without hate

For a moment

Just love.

These trees are the letters of a sacred text.

The cloudy white atmosphere, the space between the letters

The water below, the vowels that give it meaning.

And I the reader in bowed posture

Attempting to decipher the message.

Stop in my tracks…

Listening to Her in the leaves

She is crying.

She is wounded.

Too much blood

Absorbed

In the moist ground below me

Where I am treading

Is sacred.

Indian voices

Native American cries

Are not extinguished.

“Who are you to have come here.

To drink in our sacred tapestry

Without our assent?”

Time has not assuaged the violence done to us.

Nor has the grassy bank silenced our presence for centuries.

And elsewhere she screams for nations steeped in violence.

Fighting as we speak in the Holy Land

The horror has returned.

The unspeakable is present.

The images too much to bear.

She is in pain.

And inflicts pain because we failed Her.

A pogrom here a massacre there

Gets our attention.

To the demonic.

In this silent place

A forest sanctuary

There is a sanity for a moment.

A clarity intuited but not understood.

Before we return home to the front line

Her Dying Breath

She lies supine.

Gasping

Every breath a supreme effort

Her chest heaves.

Struggling

Her neck muscles assist

In the united effort to draw in oxygen

Even so, the oximeter reveals the declining saturation.

All is failing.

These agonal breaths takes me back.

Imagining my own first breath

Most likely inverted.

My tiny ankles grasped by some stern

White-starched nurse in Florence Nightingale uniform

As they would have, circa London 1950.

When was my first cry?

had she smacked my tush already?

to awaken me to what would be a long litany of smacks.

(An appropriate welcome for this naughty child’s arrival)

gasping as I must have, inhaling the cold March air,

in response to the shock and pain

a harbinger of the trauma to follow.

My muscle memory surely fails me,

It might alternatively been an angelic hand.

Realizing I had emerged from the Edenic warm amniotic safe harbor

To the cold British air:

Having been tutored in kol hatorah.

Able to see misof olam ad sof olam.

With the help of the ner daluk al roshi

Maybe it was her known as Leylah

Who swiped me on my frenulum?

Or clouted me on the head (like my German nanny Crystal)

That angelic concussive blow

That forced my first breath.

And for-getting all I had learned.

On the inside.

In this steely ICU another ping from the ventilator

Awakens me to the stark reality.

After decades of unconscious breathing

Her ventilation now increasingly faltering

What was once taken for granted now demanding every ounce of her effort.

I have failed her.

She begged me to take her home.

From this ghastly inhuman sterile space.

I failed her.

Having promised her that once she was off the pressors, I would.

But that never happened.

I watch powerless over my broken promise.

And her diminishing breath sounds.

And when the Almighty breathed into Adam’s nostrils

His first breath,

From the depths of the Holy One…

Into the lifeless flesh already formed

Awaiting this vital humor,

Suddenly Adam becomes.

Separate from nature and God.

A sentential being.

Self-aware

Of not being God

Of a self as separate,

Pulsating with the rucach chayim, inhaling the breath of life

Ensouled.

Was God smiling at him?

Did Adam feel pain?

Did he imagine his dying breath already then?

And when God buried Moshe Rabeinu

And sucked out his dying breath with a kiss.

Did He too cry, as the midrash tells us,

The divine mourner receiving nechama.

For His beloved deceased

On this isolated mountain top?

Did Moshe Rabbeinu remember his earliest cries in the basket on the Nile River?

As he gave up his ghost for the last time?

We watch her final breath.

Whereupon Sarah shrieks “Ema Ema!”

Sobbing in agony “she’s not breathing.”

But now she is calm.

There is no further struggle.

Chest does not rise.

All is silent.

The machines are silent.

The silence is deafening.

After so much struggling

The final breath had left.

A lifetime of effortless breathing has ceased.

With a final divine kiss

Misas neshika

A life dedicated to learning.

And intellectual mastery

Her legacy aligned with her forebears.

How she readily accepted the mantle of the royalty of the Beis Harav

Instilled by her father.

Now she too is gathered to her ancestors.

Who will no doubt welcome her?

Approvingly

Of her life’s trajectory

Committed above all other priorities.

Instilling in her children and grandchildren this one singular task

To perpetuate the particular avodah in torah scholarship that characterized the Beis Harav

And the ethos of Volozhin

Her Lithuanian Camelot

Demanding no less that perfection, mastery, and dedication to this singular purpose

Ignoring all other demands of modernity

Or caring not of others criticisms.

Rest calm now Ema

Your struggle is over.

No more need to climb that mountain of inhalation.

No more need to struggle and toil in learning.

Your life’s work is finally complete.

Rest easy Ema

You succeeded.

Your father and forebears approve.

They are smiling and welcome you to the yeshiva shel maalah.

All your fears and anxieties are allayed.

Rest assured.

You have left descendents.

Who are following your example and charge.

Proof of your dedication

Each one a reflection of the light you imparted.

And they received a facet of the diamond of Volozhin.

You shone forth like a beacon from a lighthouse in the fog.

In your departing breath

The Divine kissed your life, your legacy.

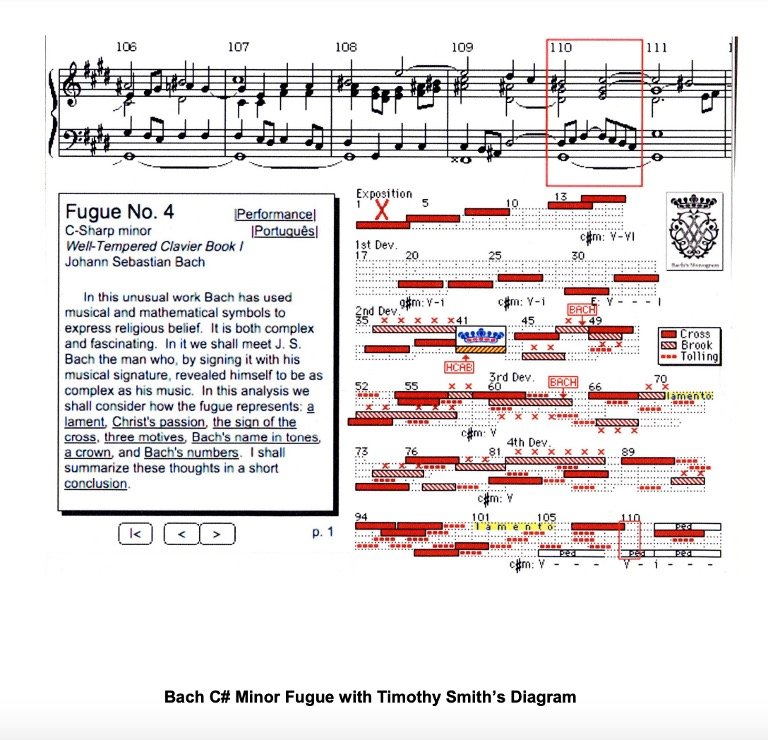

Davening In The Key of C# Minor: נפילת אפים

There is in the morning services this moment

This physical postural change

Neither standing nor sitting

But a theatrical falling onto once’s face

It’s called tachanun.

After the conclusion of the Shacharit Amida, it is customary for men to “fall on their faces” and plead before God. By doing so, they fulfill the mitzva of prayer in all three of its positions – Birkhot Keri’at Shema while sitting, Shemoneh Esrei while standing, and Taĥanun (“Supplication”) while bending forward (“Nefilat Apayim”). We learn this from our teacher Moshe, who pleaded to God to forgive Israel following the sin of the Golden Calf.

Despite its great virtue, the Sages did not ordain Nefilat Apayim as an obligatory prayer or fix its wording. Anyone who wished would add prayers of supplication while lying prostrate after reciting the Amida. Perhaps specifically because of its superior value – its expression of total submission to the Creator – it is fitting that it comes from the heart, from one’s unguarded resolve.

I fall on my non-Tefillin arm by Tachanun

The penitential confession of symbolic prostration

Burying my head in my right arm

I utter the words of penitence,

וַיֹּֽאמֶר דָּוִד אֶל־גָּד צַר־לִי מְאֹד נִפְּ֒לָה־נָּא בְיַד־יְהֹוָה כִּי־רַבִּים רַחֲמָיו וּבְ֒יַד־אָדָם אַל־אֶפֹּֽלָה

But my fallen head feels a kind of petit morte.

(Like the holy Ari suggests),

The lowest point of the service (at least physically)

And with the lowered head, the broken heart follows,

Pierced by a thousand betrayals, lies and deceits.

Then we arise to complete the davening

עָלֵֽינוּ לְשַׁבֵּֽחַ לַאֲדוֹן הַכֹּל

Swaying to recover the broken soul.

This davening seems like a sacred symphony of sorts, (or maybe a requiem?)

Each Tachanun a preparation

Each נִפְּ֒לָה־נָּא

A request to become an expert in nefilah,

Each falling a prescient training for the final irreversible fall

Into the grave.

The daily falling a ritual sacred practice of mindful dying.

וְעַל־כֵּן כְּשֶׁאָדָם נוֹפֵל, חַס וְשָׁלוֹם, לִבְחִינַת מְקוֹמוֹת אֵלּוּ, דְּהַיְנוּ לִבְחִינַת מְקוֹמוֹת הַמְטֻנָּפִים, וְנוֹפֵל לִסְפֵקוֹת וְהִרְהוּרִים וּבִלְבּוּלִים גְּדוֹלִים, וַאֲזַי מַתְחִיל לְהִסְתַּכֵּל עַל עַצְמוֹ

“Therefore, when a person falls into places of this sort, God forbid—i.e., into the “filthy places,” falling into doubts, heresy and great confusion—if he then begins examining himself and sees that he is very far from God’s glory—and as a consequence of his seeing himself far from His glory, having fallen into such places,”

Likutei Mehoran 12

Davening as Requiem

If tachanun pulls me down, down, where are the highs of this daily symphony?

Start with the initial birchat hashachar as the prelude/introit.

It’s wakeup blessings reminding us to acknowledge the miracle of awakening, opening the yes, feet on the ground, belting up, then the ultimate existential question (so soon after brushing my teeth?)

אֱלֹהַי נְשָׁמָה שֶׁנָּתַֽתָּ בִּי טְהוֹרָה הִיא

Who is this בִּי this receptacle that houses the נְשָׁמָה ?

Next comes the Kyrie with Pesukei dezimra

and the Psalmists in praising the divine,

A mellifluous group of levitical songs imagined on the steps of the Temple..

Which brings us to the Gloria/Offertory of the doxological Shema surrounded by its blessings a fore and aft, maybe (this cry traditionally prior to martyrdom), is embedded in the mystical joy of this daily pilgrimage.

And immediately followed by the deafening silence of the Amidah

The pause in the oratorio where the deafening silence in a sea of fellow worshippers binds us all more than the cacophony of individual supplications. In this silence the logorrhea ceases for a while and lips continue to mouth words inaudibly.

In the silence I am present to the grief within my sternum, and giving it space, in the silence I can almost hear the little boy crying once again, the sensation of powerlessness in the face of unjust punishment, and the rage of adults venting uncontrollably.

In this space the silent presence of Shechina

is also felt as awe pervades the shul.

The reader now begins the public amidah followed by the Sanctus of Kaddish… the angelic chorus teaching us how they praise the divine…

Which brings us back to the Confiteor of tachanun and the falling falling, through death, through the grave, through the dark night of the soul into the arms of …

“Lose yourself,

Lose yourself in this love.

When you lose yourself in this love,

you will find everything.

Lose yourself,

Lose yourself.

Do not fear this loss,

For you will rise from the earth

and embrace the endless heavens.

(Rumi chides us….)

Finally, we arise to end with Aleinu Leshabeach עָלֵֽינוּ לְשַׁבֵּֽחַ לַאֲדוֹן.

Ite missa est…

I imagine the contours of this symphonic work, its cadences, rises and falls as an orchestral score, and each section a different color,

And on different days in different keys,

Although today I prefer C# minor, Bach’s sacerdotal key,

With its foreboding tones

The entire oratorio an act of surrender and submission,

an admission of man’s inability to have conquered the inner snake,

That the experiment of human history only produced

more and more technological innovations to mass murder and genocide.

A prayer for acceptance of these facts and a surrender

to the very setup that placed in the Garden…

The initial awakening, the profession of faith,

the highs of the silent prayer followed by the

inevitable fall (from grace) in Tachanun,

and resurrection in Aleinu forms the contours of this composition.

I rise and fall with the sections, like the music of the oratorio,

like my biography, a palimpsest of human brokenness before me.

I imagine davening on the organ of Kings College Cambridge,

with the puny altar boys in their white levitical uniforms, and falsetto voices,

positing the grandeur of the cathedral and vulnerable vocal cords

that will soon break in their testosterone rush.

Each day another matin, each day the cycle of surrender

needed to break the serpentine darkness within.

R. Bachayei.

Internalizing The Divine

Making the sovev connect to the p’nimi.

Wrapped in my tallis excluding the world outside,

Strapped by my tefillin in leather chains.

Standing in the space of the divine in this sanctuary/beis midrash

With other worshippers and the devout

Swaying at their stations, their shtenders,

Surrounded by the transcendent divine.

Surrounded by the sovev kol almin.

All the spiritual opportunities are present.

The only challenge right now

Is finding the divine within…

Buried beneath the past (deceits betrayals, lies and addictions)

Lost inside a deep abdominal imagined ball of grief,

The inner serpentine voice demanding its due

The chattering monkey.

The inner kritik,

(Even Moshe strikes the rock you know! An Asherah tree for some)

My challenge remains to connect the sovev out there to the p’nimi in here.

The flawed broken soul resists,

Trapped as it is in the vice-ridden body.

Decades of revolt

Resistance to

Bending to

Bowing to

Dark authorities that controlled me.

The lost Princess (the p’nimi) screams

Her arms outstretched.

Beseeching “rescue me.”

Forgive me

Give me penitence.

Give me solace.

What is demanded each time?

Is more surrender.

Of the familiar

The routine

The comfortable

The old self must die.

And lose itself in a free fall.

Into the abyss of uncertainty

So frightening.

What is demanded each time?

Is faith, even harder, more trust, reliance,

That free falling will not end in a thud of death.

A crushing of everything this ego has born.

This biography this struggle, this failure.

Rather the trapdoor will indeed open

The path is always down down, down, into these painful dreaded spaces,

where the tears lubricate the narrow spaces,

In the grip of fear

Despite the vertigo of resentments,

Powerless in the face of this inner monster

In the fall

In the blotte

The cry of Ayeh!

Help!

I surrender!

Nailed to the crucifix on my skeletal frame.

Finally, the bottom opens up.

And I fall into the sovev.

Kaddish for Dad

Each recital punctuating the service,

Yitgadal veyitkadash…

I join my brothers in mourning.

At times I recite alone

At times with a cacophony of mourners,

Each with different cadences, accents, fluencies,

We bow and move three steps backward

Taking leave of the King.

How do I do this?

The mechanics of repetition

The prosidy of ritual

The obsessiveness of halachahic process…

So different from Mum!

Where the pain of recitation tore my heart

A serrated knife in my heart being twisted by each oseh shalom..

And the challenge of even getting through to the end.

With Dad however,

It is more a deep gnawing sadness

More in the head,

His gaping absence

No longer sitting on his perch, receiving the world

Blessing me just two weeks before he left

Responding to my singing die Lorelai

Now,

The overpowering nature of his life, his legacy and his longevity.

The memories of my childhood and the times spent with him

during the summers, his picking me up from the airport monthly

and the chats, walking to shul and back in Rehavia,

these bubble up during the monotony of the kaddish.

The weekly zoom forces us to review the recent past,

deciding among the siblings regarding disposal of the bric a brac,

the books and the contents of an apartment once lived,

And, as yet his personal items to be determined who gets what

Delaying the last agonizing decisions of his most personal items.

I imagine each Kaddish as follows,

My lowering a shovel of holy earth onto the coffin

Each kaddish another shovel-load,

Each service another lowering of earth into the grave

Despite in reality there was no box, just his body in shrouds,

But it comforts me,

Each Kaddish

Another clod of earth leaves my shovel and falls onto the coffin,

It hits the wood with the sound only those having lost loved ones recognise.

It comforts me that it will take the full 11 months of daily services-

Three times each day

To fully fill the grave itself..

The earth inside rising bit by bit to meet the surface,

And as the months progress the sound will dull

once the coffin itself is covered,

I will only see earth then, no more the Ark of Dad’s remains,

And the completion will occur when the entire gravesite

meets the ground around it,

Leaving only the shape of fresh earth, an oblong of dirt

surrounded by green, green grass.

As the earth rises to the surface ever so slowly

My acceptance and surrender to the fact and the ending

and the closure becomes internalized,

And I turn to my own life

And the inevitability of my preparation for my own mortality.

The daily aches and pains, the loss of energy and earlier fatigue

as the day winds down, all markers of decline despite good health.

I am learning that each day, each kaddish is a spiritual opportunity

to not just mourn his loss but also prepare for my own.

The spiritual path might just be a daily meditation

on the analysis of one’s path, one’s character defects,

one’s surrender to the reality of life on life’s terms,

and the surrender to the higher will of the divine.

The digging and shoveling of chthonic psychic material

is a prerequisite for opening the higher self to the light.

From panic to depression to acceptance and serenity

Each clod of earthiness covers what was, the past, the dull thud

spilling onto onto the coffin of past betrayals, deceits,

harms done to others and self- destruction.

The earth falls as does the self-constructed ego

into the reality of realization of failure, a free fall

into the brutal awareness of the picture of Dorian grey

is no longer in the attic.

Hopefully I will have accomplished the inner work

of acceptance and surrender when it comes to my turn

to be at the bottom of this opening in the earth,

Meanwhile the daily kaddish is a gift reminding me

of the ongoing painful work of shoveling and digging

into memory and trauma and healing needs attention.

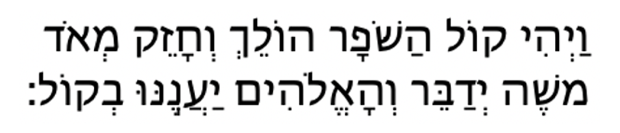

Hesped For My Father

My father was the shofar that kept on blowing

In times of grief and anger

We turn to our texts of comfort

For relief from the anguish And unbearable pain

Despite years of anticipatory grief

Never knowing whether this might be the last time

As I alighted the plane home

The fact of the ending… the end of this life.. makes it no less painful

Grief is grief.. however much, the anticipation of it.

Dad kept surprising us all!!!

Bouncing back from this or that setback!!!

He surprised us because he was a Prussian man, a disciplined man, a man of routine and moderation and undeterred by anything around him. I never saw him drunk., he always left something on his plate, he always rose early, in the british winters with no central heating all he had to do was to uncover the sheet from my big toe for shacharis…then he would see the condensation on the car window and claim “selichos weather”.. only once I saw him tucked ill in bed with the sheets over his head when I was 15…I was mortified…he never cried….he never emoted….

Not just 2 days ago he was still actively walking between his two stalwart soldiers Balu and Manjou

Rochelle ever sending us camera-ready instant videos documenting his ongoing life.

He surprised us waiting like the gentleman he always was allowing us to finish the shloshim ceremony for his mechutenes in NY Sunday

And surprising us by leaving this world on the exact yearzeit of his mechuten my father in law.

He surprised us because his life was that shofar that kept on blowing..

If I may paraphrase Batya who midrashically composed a shabbat zemir that tickled Dad ever since…yismach Shlomo bematnas.. Yismach shlomo bematnas, bematnas chelko…it captured his core…his deep satisfaction with life…his survival as testament to his victory over Hitler…the love of his life he adored ,the exotic beauty from India… his children’s accomplishments, the grandchildren and greatgrandchildren that visited him and mum on their perch…then him alone..

Despite his difficulty with verbal expression his facial gestures said it all…they never diminished…his sardonic sense of humor manifested itself with raised eyebrows, impish smile, and if he did not like something he pulled up his nose..showing us all he was all there until the end…looking down upon the world like a true Vienna schnitzel…

sometimes I would show him Mum’s picture and he looked at me forlornly..her absence tearing out his heart…other times Rochelle would show him a group black and white picture of mum becky and eric in Trafalgar square circa 1948 and he would point to Eric….and say ‘Erich” with a thick vienese german…Rochelle would refer him to that album of his life daily…page by page pricking his memory like a Megillah.. each chapter another unique historical fragment that made the mosaic of his amazing journey. That book was his sefer the sefer shel Shlomo.

He did not approve of my morbid fascination with the dark side of life and texts…why delve and kvetch …he was the survivor not me!!! He went through the war having been saved by an angel 3 times….not me!!

He always chided me after one of my dark toirahs….why do you read the pshat this way?

Why do you need to resort to midrashic fantasy…

Julian I am a happy man….no complexes …no reading into the text anything but Peshuto shel davar…in that he was a simple man…and the pashut…does not imply simplicity…it was a choice in everything he did….be straight..ramrod straight…be satisfied with what life gives…above all survive!

Shlomo yedaber Shlomo decided everything in his life

Work play communal service retirement Aliyah

Vehaelokim yaanenu bekol///////God was his partner

He survived the war…he survived a generation after the war..his life was a testament to his determination and vigor strength and vigor….

Born in a different distant epidemic

100 years ago

A survivor for a century

Surfing on the aphorisms of classical wisdom

As if we learned what he felt was necessary through his pithy wisdoms alone:

Si takuisis

Panta re

Those summers in europe in the Westminster overdrive…

Where I swear I learned in those 2 weeks from his nonstop commentary on history geography and life more than I did all year in the Hasmonean!!

Mum singing Oh the white cliffs of Dover when we returned on the ferry from Calais..

The song he composed in the Austrian tirol the zemering “baruch hashem Yisborach”

The top of the Jung Frau Yoch…he went outside alone in the thick clouds and suddenly the blue sky opened up and the brilliant sun shone down on him…he returned and told us that he had a religious experience…so uncharacteristic of him to indulge in such spiritual excesses!

Always with humor. Always looking on the bright side of life…

His humor was continental.. not British.. he could not fathom my love of Monty Python….

His friends were mainly survivors…Uncle Kay, his partner Ernest Strauss Max Landau..Mr Wolf…the Viennese gabbai who taught him to be a world class gabbai….people would come ot him with their problems…even his co-Gabbai Rozenthal would accompany him home despite living in Woodside Park,

His sense of right and morality earned him consistent promotions from gabbai to VP to President of the shul…to national prominence in governing the Federation on their board and running the kashrus branch that made the name KF respectable to all.

His courage in hiring the first ever Chabad Rabbi to a British synagogue pulpit in Rabbi Telzner for whom his love never faded..because he saw in him the erlichkeit…never mind the trappings of nusach…or even ideology…

His ability to handle the unruly and offended in shul,,,,and in the box during anim zemiros listening to the president tell him off color jokes with his thick cockney accent and Dad trying to hold back the giggles…

His work life and his adoring employees who he had earned their love by secretly paying for their debts, his honesty in business and where his competitors were getting cheaper plastics from Germany he resisted…

I would come in to England on my way to work in NY from Israel, he always picked me up from Heathrow never ever complained and took me back after the weekend with them…no matter what was on his plate..how can I ever repay that kindness….

His adoration and tolerance of Mum who was not an easy personality!!!!

And the two of the on their perch in trumpeldor….always hand in hand…he admired her violin fingers!! Worthy of a Michalangelo sculpture,

On this perch …Where all the world would come ot pay homage

Surrounded by mostly their artwork on the walls

Dad helping mum with her bookbinding, the leathers the quality the color the thickness calligraphy and whatever new craft she happened to choose…

Music saturated the home….Mum a virtuosi would listen to you-tubes of various performers

Critiquing them…and dad would look o dutifully…for he had his own choice pieces..

His favorite melodies he responded to even 2 weeks ago

Eric would play La Campanella …I sang… he nodded

Torselli!! Heinrich Heine…de Lorelai..these never left him

Ich weiss nicht, was soll es bedeuten,

Dass ich so traurig bin;

Ein Märchen aus alten Zeiten,

Das kommt mir nicht aus dem Sinn.

Having born witness to Hitler’s march into Vienna

Kindertransport

Internment

The love of his life

Starting a family

Communal work

Synagogue warden, President,

National prominence, VP federation of Synagogues

Aliyah

Scrabble with Rivkie

Calisthenics with Ganady

Hot chocolate with Rochelle

How to thank those who cared for him

Balu Manju

Devorah whose skill and sensitivity to his needs kept him alive

Dr Simon,,,whose clinical judgment and balanced understanding of medicine and halacha equals anything we have in the US..

Dr Djemal…a general practitioner who reflects the best of the NHS and whose care and love of her patients is legendary…

My brother who took care of the finances and weighed dad measured his body flluids and indeces on a spreadsheet that is worthy of publishing! Keeping us all up to date with variations in fluid intake output, weight HB HCT etc etc etc….

His Friday visits to Dad with the weekly foto of Dad emerging from the shower in his Harrods white robe looking regally into the camera …said it all…

Debs who would fly in and swoop down with her medical experience in helping those with cancer in Memorial Sloan Kettering would wake us up to complacency and usually correctly remind us of this or that medical change. It was easy for Debs and I to come in and then leave on our visits..it was a different story being there for the daily grind…

But beyond and beyond and beyond is my darling twin sister Rochelle…whose place in Gan Eden is assured….who loved Dad despite his stubbornness, his obstinancy…who pushged him to eat and get nourished,,,who knew every change in his condition before it happened…who worried incessantly about this or that…it was Rochelle we owe his longevity…insisting on taking him out for hot chocolate with a mountain of whipped cream 5pm every day…who knew his likes and dislikes…

I know not when he began to blow shofar

In Tatura British Internment camp? Autsralia

Prior in Vienna?

But at 101 he continued to blow

He loved to entertain his guests

(despite Mum calling it “showing off”)

Even when `cognitive articulations fail

As if his shofar blowing

Represents his will to breath

The serpentine shofar bending to his will

As if he finally tamed the inner snake of desire

And the outer monster of this century

The power of his sound

The power of his Prussian will

The power of his survival

Memories of his blowing in Finchley Central shul in the 60’s

Those last few kolos

We were on tenterhooks as kids

Carrying the shame of his failure

And the pride of his success

What began the century

Now ends it

The shofar heralding its onset and its end?

The jubilee of his life now bookended?

How he survived all of this,

This horrific century

Doggedly refusing to surrender

To the rules of others

His own iron will

Of moderation

Health, exercise

Care of the body and mind

No extremes mind you.

His Aliyah as a final arrival to the field of dreams

His delight in walking the streets unabashed of his yarmulke

“I never have to look over my shoulder again” he quipped

Impossible in Europe

A microscopic reflection of what has taken place in the miracle of Zionism.

But also, an inner protection, a survivor’s immune response to tragedy

Through walling off the emotions of loss

And the price one pays for that!

And the demands of discipline and results from children

No room for failure

No expression of emotion allowed

Especially crying….my earliest recollection was in Stamford Hill N16 around 1953 yom kippur?

I must have been crying during the kedusha

Will never forget that stern look…

As I watch him blowing

It is as if he is telling me

I may not express myself

I may not tell you my feelings

I may not divulge my inner thoughts, I never did,

But here is my legacy

Listen to the power

Listen to the cadence the pitch the perfection

Here

This is what I leave my children

The memory of this sound

The sound that grows stronger and stronger

The sound of the jubilee

In this land of Jubilees

The optimism of the survivor

This spiritual immunity I give to you

To survive.

This deep hole in the heart

The pit in the stomach The deep sadness

There is some comfort in these texts The ones that arise…

Do not go gentle into that good night,

Old age should burn and rave at close of day;

Rage, rage against the dying of the light.

Though wise men at their end know dark is right,

Because their words had forked no lightning they

Do not go gentle into that good night.

Thanksgiving Sunrise Surfside FL 2022