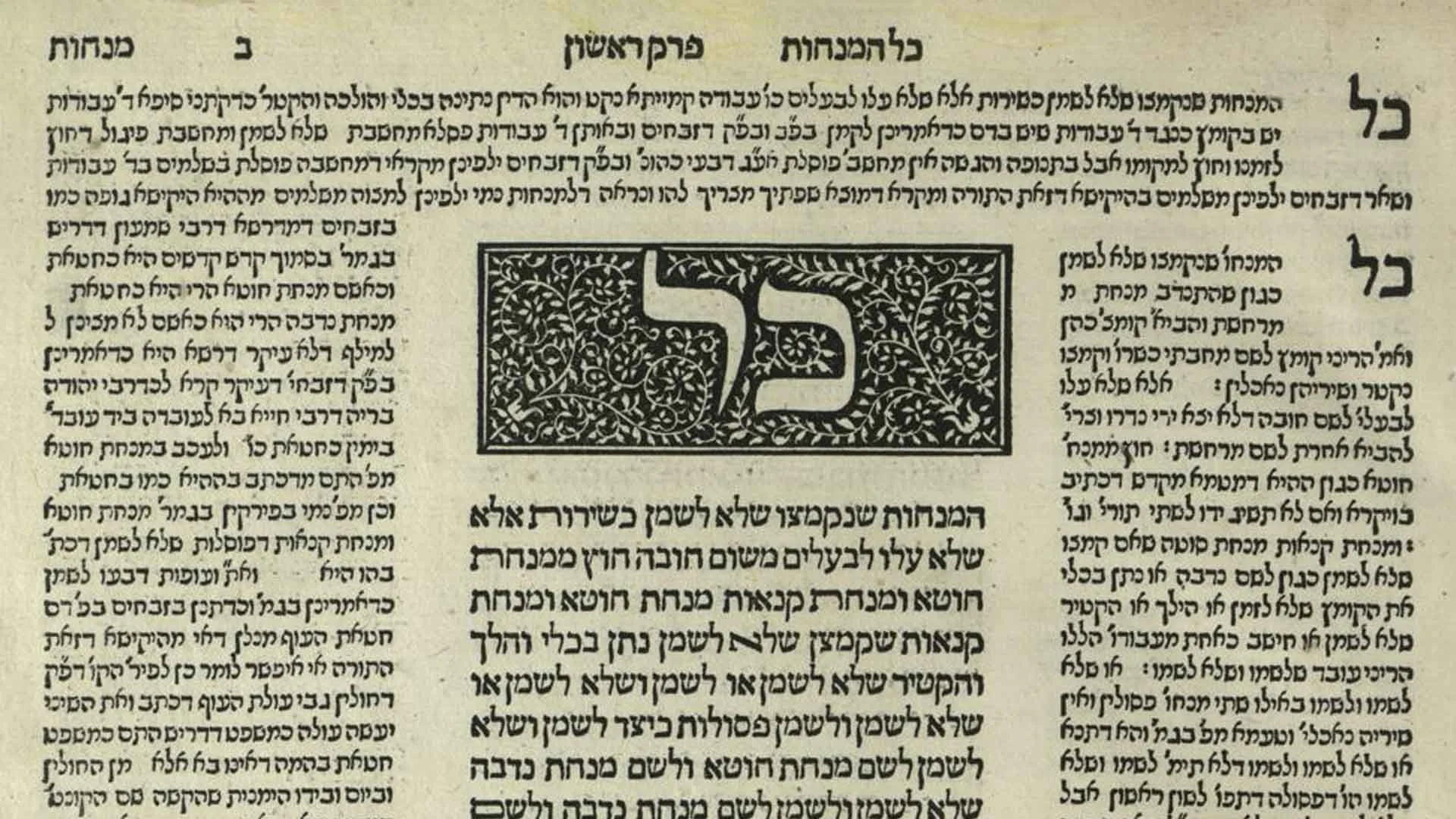

For the source text click/tap here: Menachot 11

To download, click/tap here: PDF

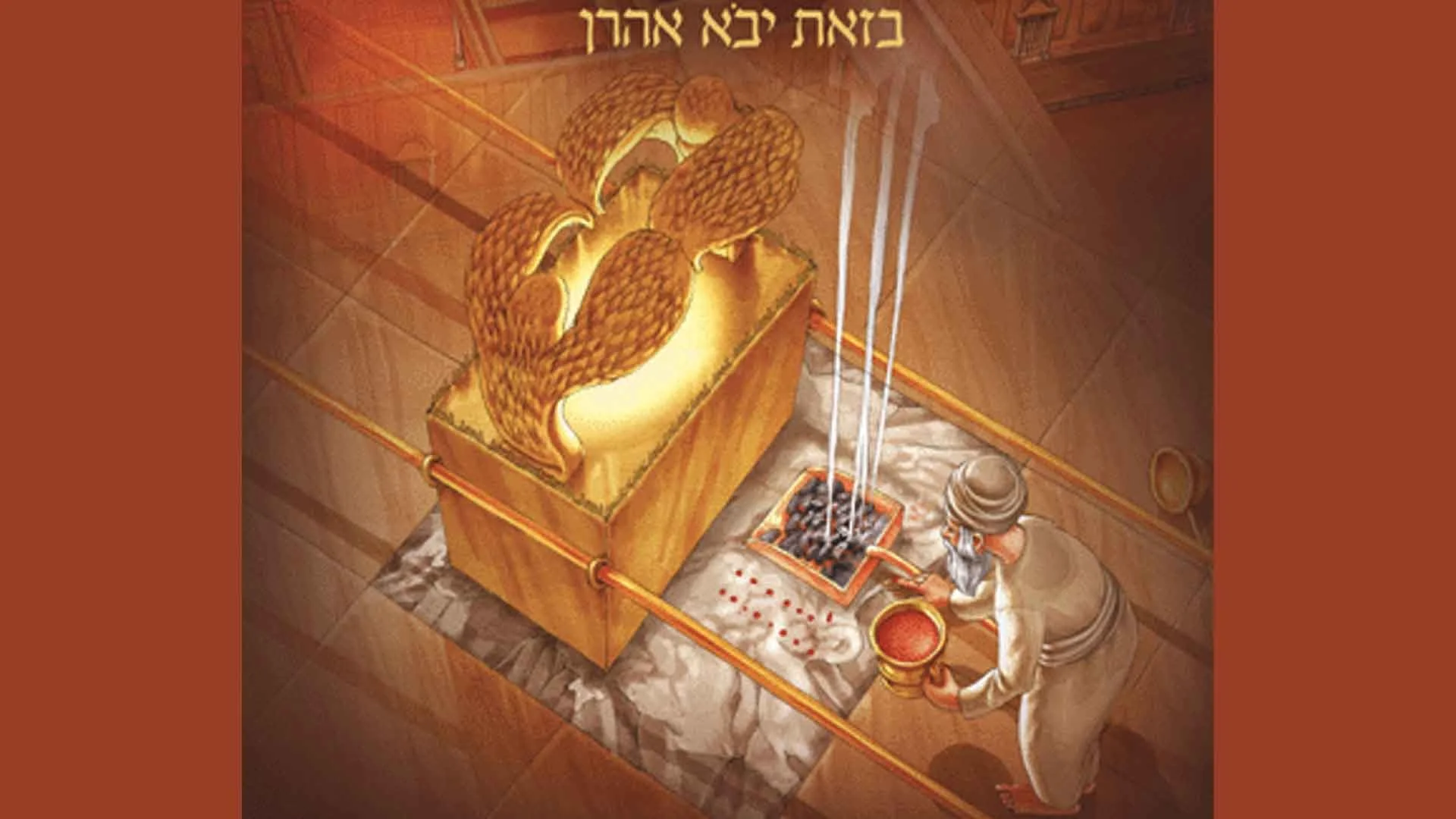

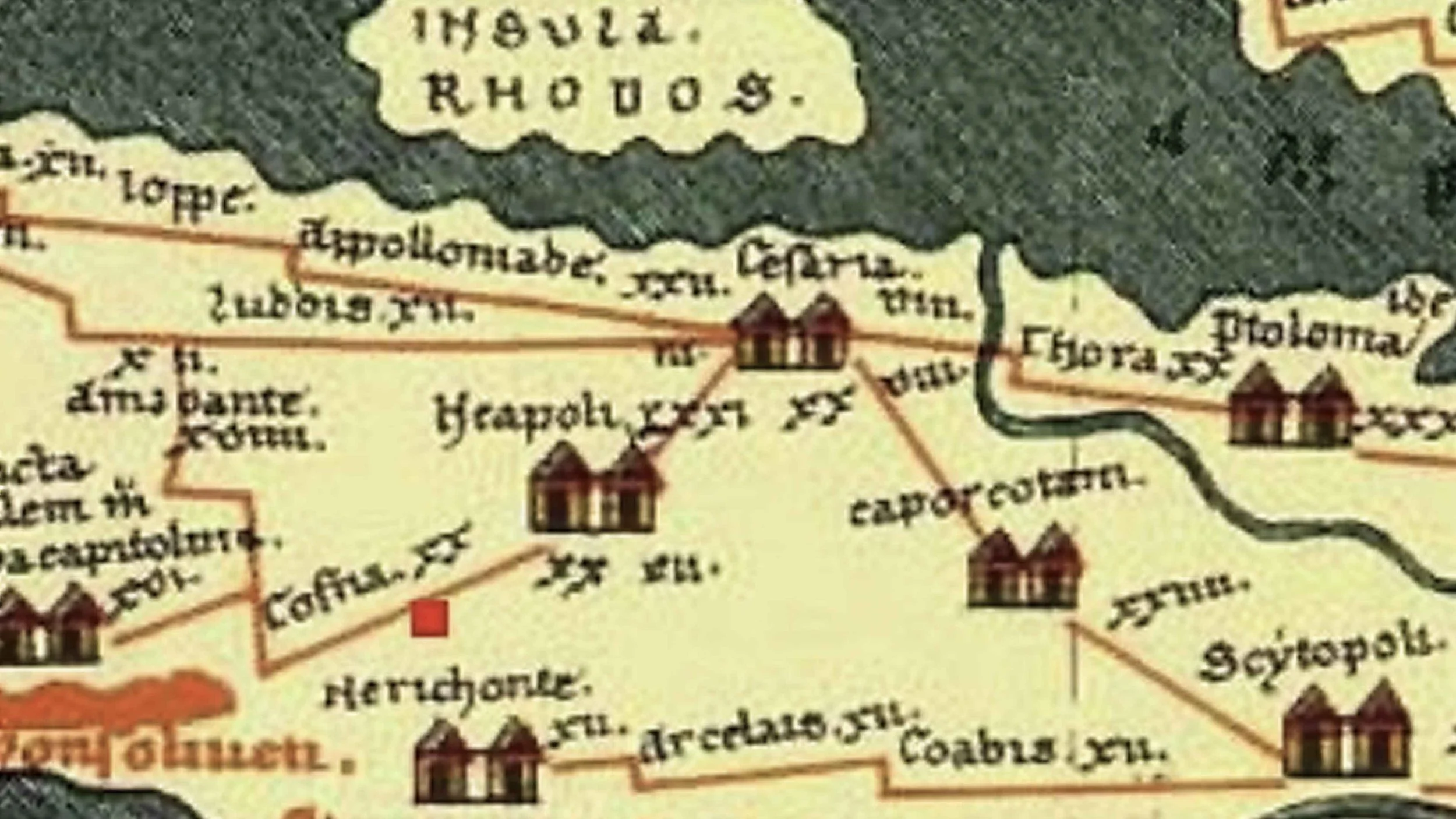

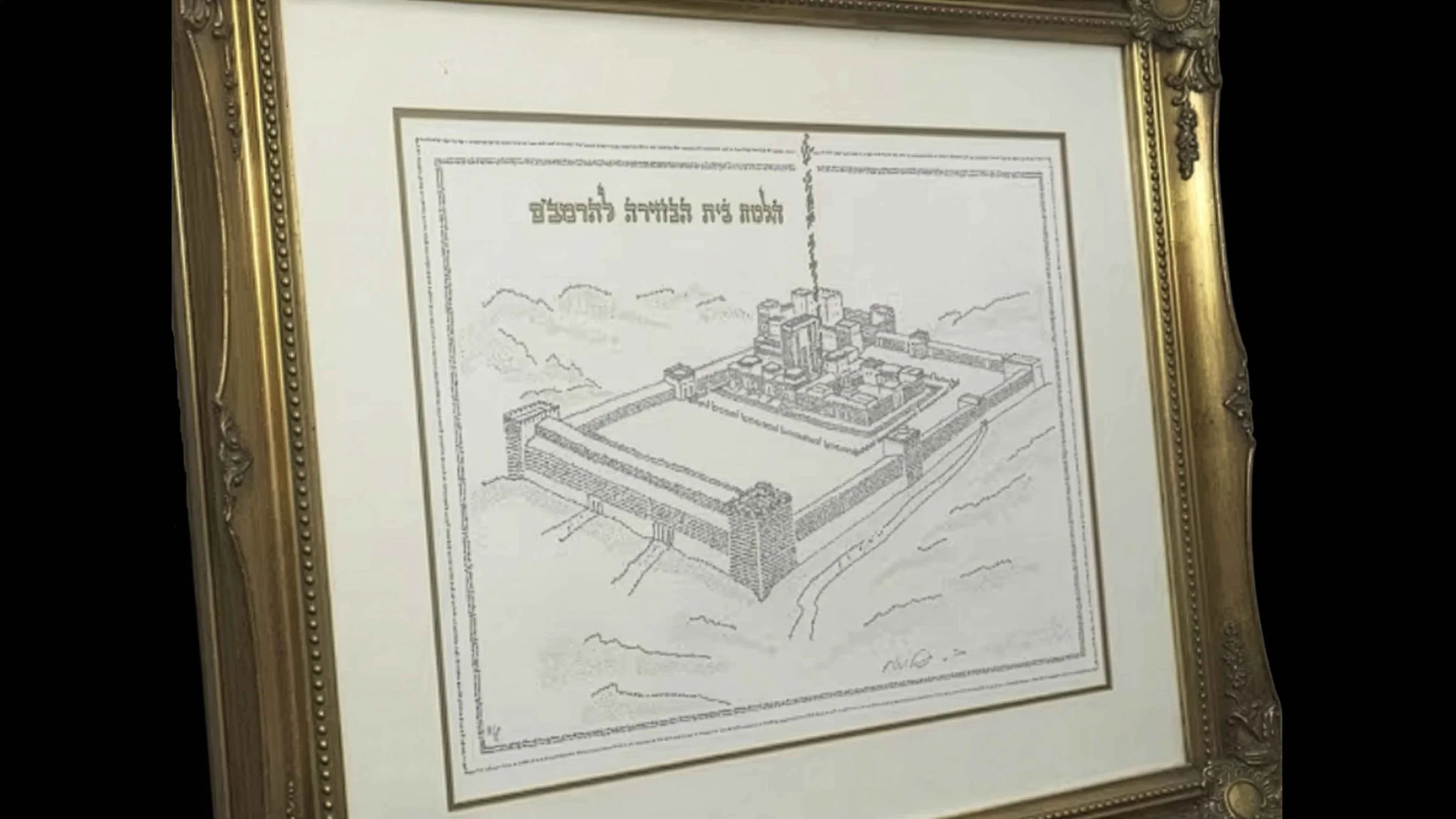

As we have learned, one of the central practices that must be done to meal offerings brought to the Temple is kemitza – when the kohen takes a fistful of the flour-oil-frankincense mixture – and places it in a keli sharet – one of the Temple vessels – as preparation for sacrifice on the altar. Kemitza is described on our daf where we learn that it was considered one of the most difficult of the sacrificial services.

Rava suggests that kemitza was done by taking a full handful of the meal offering mixture in a normal manner. The Gemara raises an objection from a baraita that names each of the five fingers on a person’s hand; they are zeret (pinky), kemitza (ring finger), amah (middle finger), etzba (index finger) and gudal (thumb). The placement of the kemitza in this list seems to indicate that a kemitza is not performed with all five fingers.

We explore the world of frankincense historically and literary.