For the source text click/tap here: Menachot 58

To download, click/tap here: PDF

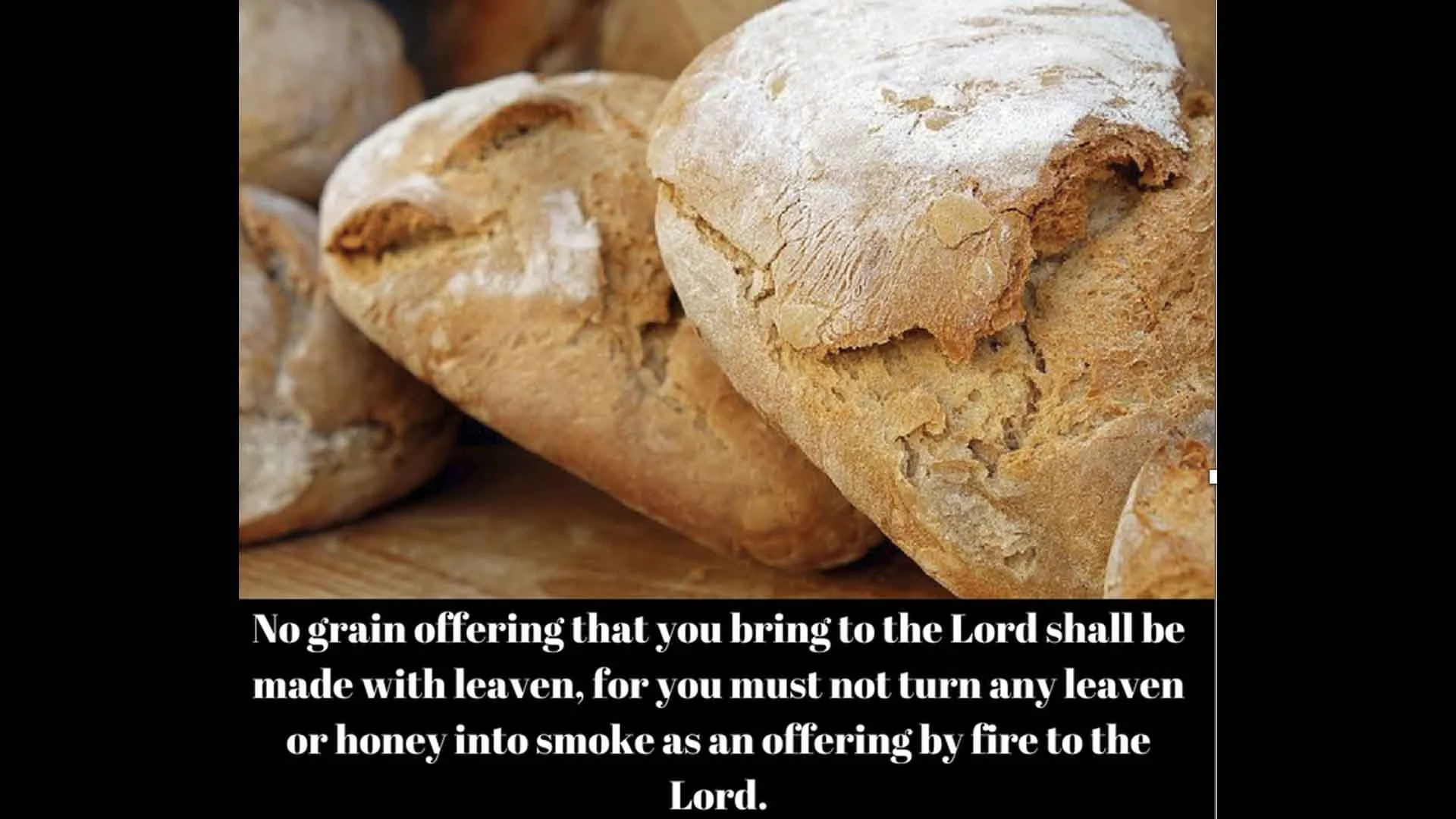

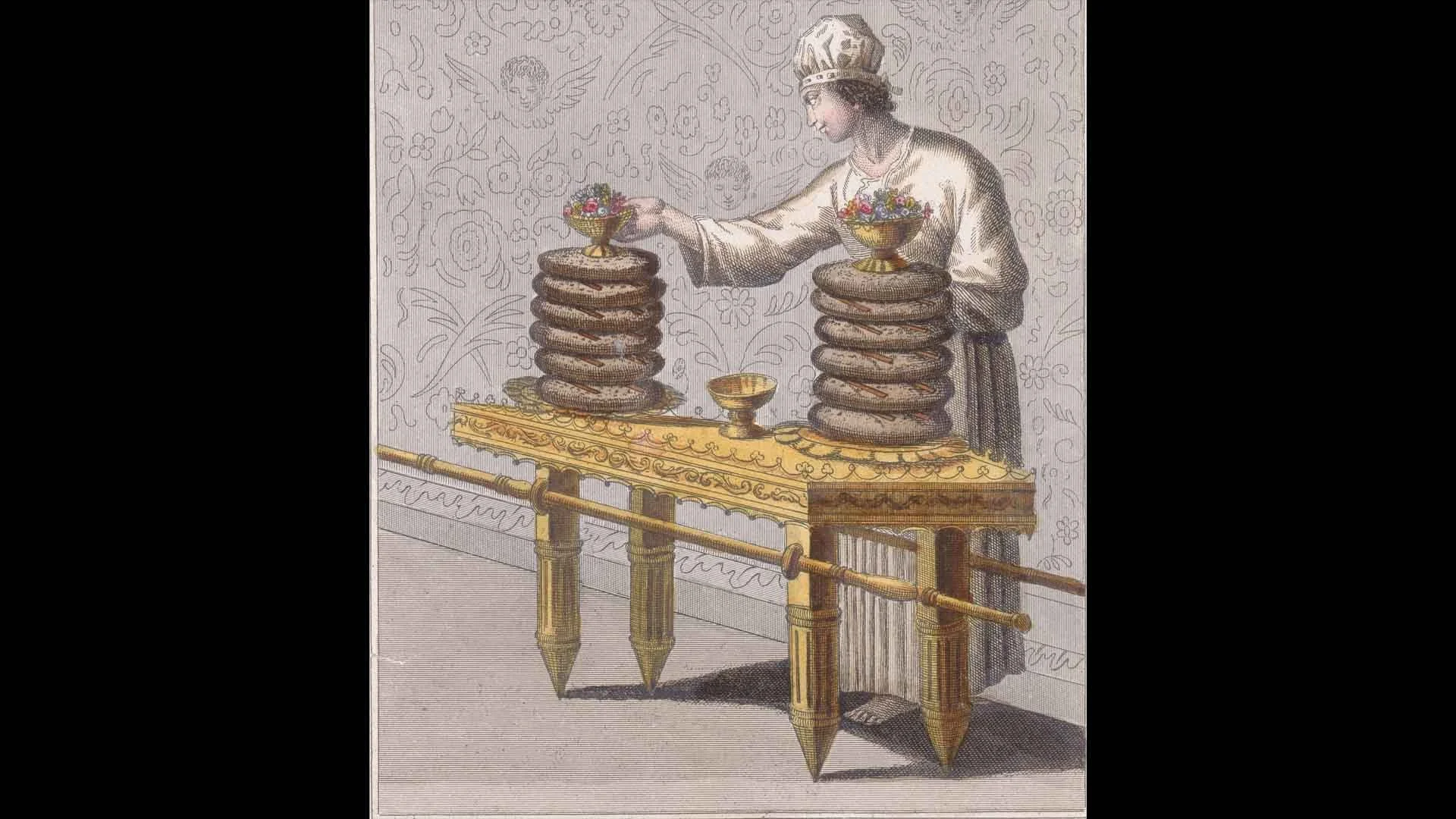

According to the Torah, two things cannot be brought as meal offerings – se’or, leaven, and dvash, honey (see Vayikra 2:11). The Gemara on our daf quotes a baraita that explains that both of these must be emphasized since each one contains something that we would not know based on the other. Se’or is occasionally permitted in the Temple, e.g. the shtei ha-leḥem – the two loaves brought on Shavuot – but dvash is never permitted in the Temple. Dvash can be mixed with the remnants of meal offerings that are eaten, but those remnants cannot be allowed to become leavened.

Why are se’or and dvash forbidden?

In his commentary on the Torah, the Ramban suggests that pagan sacrifice usually included offerings that had risen and become leavened, and were mixed with honey, leading the Torah to forbid such practices.

The Talmudic sugya on our daf arises from a deceptively simple biblical prohibition. Leviticus 2:11 states: 'No meal offering that you offer to the Lord shall be made with leaven; for you shall burn no leaven nor any honey as an offering made by fire to the Lord.' The verse seems clear enough. Yet the Gemara's engagement with this text in tractate Menahot opens onto a sustained legal inquiry that encompasses the minimum quantity of a prohibition, the identity of substances in mixed states, and the structural conditions under which a biblical prohibition can generate corporal punishment.