Avir Ha-Mizbeach

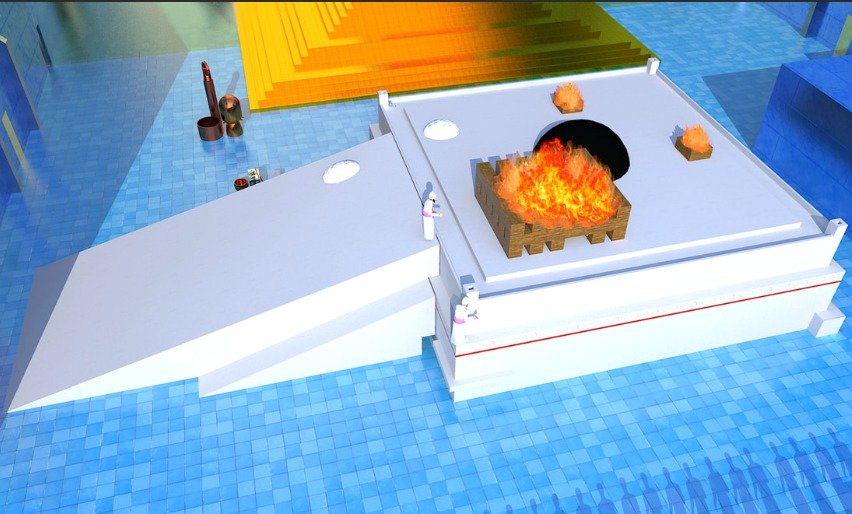

My heart is the altar,

a rough stone in a quiet room,

where I lay down the things I’ve carried

too tightly,

too long—

old vows,

unspoken wants,

the stiff weight of my own expectations.

I gather them like wood,

trembling and dry,

and place them one by one

on the altar of my chest.

There is no priest here,

no knife,

only the courage to release the shape

of the life I thought I needed.

The fire comes softly—

a breath,

a letting go,

a whispered yes to what is.

It flickers first at the edges

then burns through the tangled heap

of what I once demanded from the world

and from myself.

As it burns,

the smoke rises—

thin strands of prayer

ascending into the air above me.

And the air, that ancient air,

the avir ha-mizbeach,

grows holy.

For sanctity is not in the offering

but in the space it frees;

not in the flames

but in the trembling air that receives them.

And so I watch my expectations

turn to breath,

to heat,

to nothing—

yet not to nothing,

for they rise

and rise

and rise

to a place I cannot see

but can feel—

a widening,

a clearing,

a sacredness overhead

that was waiting for me all along.

May the air above this heart

remember what I surrendered,

and return to me

only what is true,

only what is needed,

only what can live.

For the altar is mine,

but the rising—

the rising belongs to God.

Painting by Daniel von Weinberger

For the Wreckage and the Remaining Light

I am seventy-five

and the world I tried to conquer

lies behind me like a broken map—

creases where I folded it too hard,

tears where I dragged others with me,

ink smeared by the storms I refused to name.

I chased kingdoms that dissolved at my touch,

chased honor like a frightened soldier,

chased love with the blunt weapons

of a man afraid of softness.

And in the chase

I left scars on the ones I meant to protect.

Time has turned my victories to dust,

and the dust into questions.

Now the nights are long enough

that ghosts rise

not to accuse,

but to remind.

They say:

You lived like a man marching,

but those you loved

needed a man listening.

There is grief in this age—

a grief without enemy or battlefield—

the grief of memory,

of sudden tenderness for people I hurt

while believing I was building a future.

We are told

men in their final chapters want peace,

respect,

freedom,

companionship,

and trust.

But I would add a sixth:

absolution—

not from heaven,

but from ourselves.

At seventy-five I find myself in solitude,

not the isolation of defeat,

but the solitude that feels like

a small room God left unlocked

so I could finally sit with my own soul

and not flee.

In this solitude,

time becomes sacred again,

as I once wrote—

a kind of tzimtzum in reverse—

God expanding into the cracks

I spent a lifetime ignoring.

Here I can finally feel the wreckage

without drowning in it,

touch the scars without reopening them.

If there is redemption for men like me,

it lives not in what we conquered,

but in what we now choose to release.

The sons and daughters of my striving

carry marks I never intended,

but perhaps the final kindness of age

is the chance to say:

I see it now.

I see you now.

I am seventy-five,

and though the world I built leans crooked,

something in me

leans toward mercy.

Maybe this is what it means to grow old—

to stop asking for victory

and start asking for forgiveness.

And maybe,

if the heart is willing,

even the wreckage can glow.

Flobbadob!

A Neurologist's Reflection on Bill and Ben, the Flowerpot Men

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o6zNwBTLSWU&t

I was three years old, sitting cross-legged on a threadbare carpet in London, my nose practically pressed against a ten-inch black-and-white television screen—that miraculous portal that flickered with all the gravitas of a campfire in the corner of our modest flat. The year was somewhere in the early 1950s, and I was about to meet two flowerpot men who would shape my understanding of language, absurdity, and ultimately, the medicine I would practice half a century later.

Still from original BBC series, with Little Weed

The Garden at the Bottom of Consciousness

Bill and Ben lived at the bottom of a garden. Not a grand garden, mind you—no Hampton Court topiary or Versailles formality—just an ordinary English garden with a slightly negligent gardener who had the good sense to leave regularly, allowing the magic to happen. When he departed, these two little chaps emerged from their flowerpots like thoughts rising from the unconscious, speaking in that glorious nonsense language they called "Oddle Poddle."

Flobbadob! It meant everything and nothing. Hello, goodbye, perhaps "I say, old chap, this is rather extraordinary, isn't it?" All compressed into three syllables of pure semantic rebellion. As a three-year-old, I found this deeply satisfying. As a seventy-five-year-old neurologist, I find it profoundly satisfying. Because Bill and Ben understood something that took me decades of medical practice to fully appreciate: sometimes the best communication transcends conventional language entirely.

String Puppets and the Theater of Pain

They were string puppets, these flowerpot philosophers, jerking about the garden with all the mechanical grace of a patient recovering from a stroke. Maria Bird voiced both of them, which means that Bill and Ben were essentially having conversations with themselves—a neat trick that every chronic pain patient knows intimately. The internal dialogue between the part that hurts and the part that observes the hurting, between hope and despair, between "I can manage this" and "I absolutely cannot manage this."

Weed, their companion, was a sunflower who spoke by having air blown through a reed. Think about that for a moment. A puppet plant whose voice was literally just wind through a tube, and yet we children understood perfectly what Weed was communicating. We didn't need a translation app or a medical interpreter. We just knew. This is precisely what I try to teach medical students about pain assessment: sometimes a wince communicates more than a ten-point numerical scale. Sometimes "flobbadob" contains more diagnostic information than a detailed pain history.

The Fifteen-Minute Consultation

Each episode lasted about fifteen minutes. Fifteen minutes! In that time, Bill and Ben would have an adventure, solve a problem, probably misunderstand something, reconcile, and return to their pots before the gardener came back. Fifteen minutes of complete narrative arc, character development, conflict resolution, and moral instruction.

Now, I don't know if you've looked at the state of modern healthcare recently, but fifteen minutes is precisely what we get with most patients. Fifteen minutes to understand decades of accumulated suffering, to distinguish between nociceptive and neuropathic pain, to account for psychological overlay, to prescribe, to reassure, to heal. Bill and Ben managed entire existential adventures in that time. Perhaps we neurologists should take notes.

The secret, I think, was their economy of expression. When you can only say "flobbadob," "flobbalob," and "weeeeed," you become remarkably efficient. You get to the point. This is what I tell my chronic pain patients: Be a flowerpot man. Tell me the essential thing. Not the entire encyclopedia of your suffering, just the flobbadob of it.

The Gibberish Cure

Let me confess something that might get me drummed out of the American Academy of Neurology: sometimes, when I'm explaining complex pain pathways to patients—the difference between A-delta fibers and C fibers, the role of the dorsal horn, the descending inhibitory pathways—I see their eyes glaze over in exactly the way mine must have glazed over during undergraduate organic chemistry. And I think: What they're hearing is Oddle Poddle.

Not because they're unintelligent, but because pain is fundamentally ineffable. It resists precise language. McGill Pain Questionnaire be damned—when you're in the grip of it, it's all just "ow ow ow" in different registers. So sometimes I abandon the neuroscience lecture and I simply say: "It hurts like blazes, doesn't it?" And they nod vigorously, gratefully, because I've spoken their language. Flobbadob. Message received.

Bill and Ben taught me that humor doesn't trivialize suffering—it contextualizes it. Those two little men lived in a world where nothing was quite right (they were flowerpots, for heaven's sake, achieving consciousness and mobility for reasons never explained), yet they approached each day with curiosity and delight. Their adventures were humble: investigating a mysterious object (usually something mundane like a glove or a trowel), being startled by Weed, resolving some tiny conflict, and going home satisfied.

The Lost Episodes and Lost Patients

Here's a melancholy fact: many of the original episodes were lost. Wiped, taped over, or simply deteriorated beyond recognition. The BBC didn't think anyone would care about string puppets speaking gibberish decades later. They were wrong, of course. In 2019, the BBC Archives painstakingly restored some of these lost episodes, digitizing what remained of Bill and Ben's small adventures.

As someone who's practiced neurology and pain management for over fifty years, I think often about my "lost episodes"—the patients I couldn't help, the diagnoses I missed, the chronic pain cases that defeated me. You can't restore those. There's no archive that will bring back the patients who suffered needlessly because I didn't know what I didn't know. But what Bill and Ben taught me—on that scratchy black-and-white screen in 1952—was that you show up anyway. You emerge from your flowerpot. You say flobbadob with conviction. You have your small adventure. And then you go back to your pot and wait for tomorrow.

The Postwar Gentleness

Bill and Ben embodied what the history books call "the gentleness and optimism of postwar British culture." This always makes me laugh, because the Britain I remember from the early 1950s was still rationing butter and dealing with bombsite rubble. "Gentleness and optimism" is rather generous language for "we're all traumatized but trying to pretend we're not."

But perhaps that's precisely why Bill and Ben mattered. They offered fifteen minutes of gentle absurdity in a world that had recently been rather harshly sensible. They said: Look, none of this makes sense anyway. You might as well be a flowerpot man. At least you'll have adventures.

I think about this with my chronic pain patients, many of whom are living through their own postwar periods—post-surgery, post-accident, post-diagnosis. They're dealing with their own rubble. And sometimes what they need isn't another medication adjustment or nerve block. Sometimes they need permission to speak Oddle Poddle for a while. To be bewildered. To not have to make sense. To just say flobbadob and have someone understand.

The 2001 Revival and the Problem of Nostalgia

In 2001, the BBC revived Bill and Ben as a stop-motion animation for CBeebies. They added new characters—Thistle and Boo (names that sound like either garden companions or prescription medications, I'm never quite sure which). The animation was smooth, colorful, high-definition. Very professional.

And yet... something was lost. The jerky string puppets had a quality that the smooth stop-motion couldn't replicate. They looked like they might hurt—stiff, awkward, struggling against their strings. Which is, of course, what embodied existence feels like for most of us, particularly as we age, particularly when we're in pain. We're all string puppets giving it our best flobbadob.

The revival was nice. But it was too nice. The original Bill and Ben existed in that productive space between functioning and struggling, between control and chaos, between sense and nonsense. They were liminal creatures. The new ones just looked like they were having a nice time in a garden. Which is fine, but it's not the same as living at the bottom of a garden, waiting for the gardener to leave so you can finally be.

Medical Education and the Flute and Xylophone Method

The original show was accompanied by flute and xylophone music. Simple, repetitive, almost hypnotic. No grand orchestral sweeps, no emotional manipulation through strings and timpani. Just: flute, xylophone, message.

This is how I wish medical education worked. Instead of the grand orchestral complexity of cellular biology, pharmacodynamics, and evidence-based guidelines, sometimes I want to just play two notes and say: Pain bad. Less pain good. Here's how.

Obviously, this is insufficient for board certification. But it might be sufficient for compassion. Bill and Ben didn't have access to advanced therapeutics. They had each other, they had Weed, and they had their capacity for wonder. Yet they managed to turn simple garden encounters into meaningful experiences.

Some of my most successful therapeutic relationships have operated on the Bill and Ben model: we don't understand everything, we're working with limited resources, we're going to encounter confusing situations, but we'll face them together and we'll try to maintain some humor about it. Flobbadob, let's see what we can do.

The Cultural Icon Problem

The history tells us that "Bill and Ben became cultural icons of British children's television." This is both true and absurd. They were flowerpots. Speaking nonsense. For fifteen minutes at a time. Yet they entered popular speech, were referenced in British comedy, and became symbolic of "a simpler era."

There's a tendency in medicine to romanticize "simpler" approaches to care—the country doctor with his black bag, making house calls, knowing everyone in the village. We forget that "simpler" often meant "people died of treatable conditions." But there was something in that model worth preserving: the sense that the healer and the patient were in the same garden together, speaking a common language, even if that language was occasionally gibberish.

Bill and Ben became icons not because they were sophisticated or grand, but because they were recognizable. Every child understood what it was like to be small in a big world, to not quite grasp what was happening, to need a friend, to speak in a private language. That's universal. That's why they endured.

In pain medicine, our icons are different—Melzack and Wall's gate control theory, the WHO pain ladder, the biopsychosocial model. These are important. But sometimes I think we could use a few more flowerpot men in our iconography. Figures who remind us that being bewildered is normal, that not having all the answers is the human condition, that flobbadob is a perfectly reasonable response to suffering.

The Weed Principle

Let's talk about Weed. Weed was a sunflower who couldn't speak English, only communicate through that reed-blown wheeze. Weed was neither Bill nor Ben—Weed was the garden itself, somehow sentient, somehow involved, but definitively other.

In every clinical encounter, there's a Weed. It's the chronic pain itself—this third presence in the room that neither patient nor physician fully controls or understands, but which definitely has opinions and makes itself heard. You can't have a conversation about pain without pain being part of the conversation. It wheezes and interrupts and sometimes helps and sometimes hinders.

Bill and Ben never tried to eliminate Weed. They didn't uproot the sunflower or spray it with herbicide (although, let's be honest, their botanical gardening practices were questionable at best). They simply accommodated Weed. They worked around it. They included it in their adventures. Weed was part of the ecosystem.

This is closer to good pain management than our war metaphors—"fighting pain," "battling chronic conditions," "defeating symptoms." Sometimes you just need to say, "Right, there's Weed. Weed's here. Let's have our adventure anyway." Flobbadob, Weed. We see you.

The Ten-Inch Screen and the Vast World

That television was ten inches diagonal. Black and white. The reception was probably terrible. And yet through that tiny, flickering portal, I encountered a universe. Bill and Ben's garden was small—smaller, probably, than our actual garden—but it was limitless in possibility.

This is the paradox I've observed in chronic pain patients: their world often shrinks to the dimensions of their suffering—this joint, this nerve, this daily routine. Yet within that tiny space, there can be immense complexity, tragedy, heroism, humor, despair, and hope. A fifteen-minute consultation is a ten-inch screen. But if we're paying attention, if we speak each other's language, if we're willing to encounter some nonsense along the way, it can contain multitudes.

The Real Flowerpots

Here's a detail that delights me: the original puppets were made from real flowerpots. Not fancy theatrical materials designed to look like flowerpots. Just actual terracotta pots from a garden center, probably costing a few shillings, with faces painted on and some cloth for little bodies.

There's something profound here about working with what you have, about finding the sacred in the ordinary, about transformation that doesn't require transcendence—just imagination and commitment. The flowerpots didn't become Bill and Ben. They always were Bill and Ben. They just needed someone to see it and give them voice.

My patients aren't broken people who need to be fixed. They're people—complete, complex, inherently valuable—who happen to be experiencing pain. The therapeutic task isn't to transform them into something other than what they are. It's to help them see that even in their flowerpot existence, even in their limited garden, even speaking Oddle Poddle, they have adventures available to them. They have agency. They have story.

Conclusion: A Lifetime Later

When I think about what has most informed my practice—what has helped me sit with suffering, maintain hope, and occasionally achieve healing—I keep coming back to two flowerpot men on a ten-inch black-and-white screen, speaking a language that made no sense and perfect sense simultaneously.

Flobbadob, indeed.

If I could rewrite the medical school curriculum, I'd include a module on Bill and Ben. Not as nostalgia or comic relief, but as serious clinical instruction:

· Sometimes the best communication transcends conventional language

· Economy of expression is a clinical virtue

· Humor doesn't minimize suffering—it makes suffering bearable

· Gentleness in the face of chaos is revolutionary

· Working with limited resources requires creativity, not despair

· The bewildered can still have adventures

· Not everything needs to make sense to be meaningful

· Accommodation beats elimination

· Small screens can contain vast worlds

· Real flowerpots are sufficient

When I'm with a patient who's been through the medical mill—seen twelve specialists, tried forty medications, undergone procedures that promised everything and delivered nothing, who sits in my office radiating exhaustion and fading hope—I sometimes think: We're both flowerpot men here. We're speaking Oddle Poddle. But we're speaking it together.

And occasionally, just occasionally, that's enough. The gardener leaves. We emerge from our pots. We have a small adventure. We return, somehow slightly changed. We wait for tomorrow.

Flobbadob, my friends. Flobbadob.

When I lecture to medical students about pain management, I usually end with this: You're going to encounter suffering that doesn't respond to your interventions. You're going to face patients whose pain is immune to your best pharmacology, your most skilled procedures, your most compassionate presence. You will feel helpless. You will doubt your competence. You will wonder if you're doing any good at all.

In those moments, remember that showing up is itself therapeutic. Witnessing is itself healing. Speaking the patient's language—even if that language is "it hurts" in fifty different ways—is itself medicine.

Be a flowerpot man. Live at the bottom of the garden. Wait for the gardener to leave. Emerge. Have your small adventure. Speak your gibberish with conviction. Include Weed. And then go back to your pot, knowing you've done what flowerpot men do.

It won't feel like enough. But Bill and Ben taught me: enough is not the point. Showing up is the point.

And maybe, just maybe, flobbadob is the prayer we've been looking for all along.

https://x.com/Radiojottings/status/1604503000776572932?cxt=HHwWiICwpc2-q8QsAAAA

Addendum

Etrog Men

This year on Succot I placed two etrog survivors in my silver case with googly eyes.

Bill and Ben the Etrog men filled me with nostalgia for flobbadob

— Dr. Julian Ungar-Sargon, MD, PhD

November 2025

Etrog

Rounded at the top,

a crown of perfection —

gleaming yellow-gold,

polished by the trembling of my hands.

Here I see the dream I was meant to bear:

my ideals,

my people’s yearning made flesh in fruit,

smooth with impossible completion.

Then, the narrowing —

the gartel cinched around its waist,

a belt of humility,

separating breath from breath,

the sacred air above

from the profane murmur below.

It is the line I draw each morning

between prayer and practice,

between the soul’s reach

and the hunger of the body.

Beneath, the lower half —

rough, pocked, scarred with human failure.

Here is the residue of my unlearned holiness,

the instincts that root me

in the soil of longing.

Here I am most myself,

half-formed, half-fallen,

still bound to the upper light

by that thin, indented gartel

which whispers,

even separation is a kind of connection.

My esrog is me

And I am it

And it is in my dreams

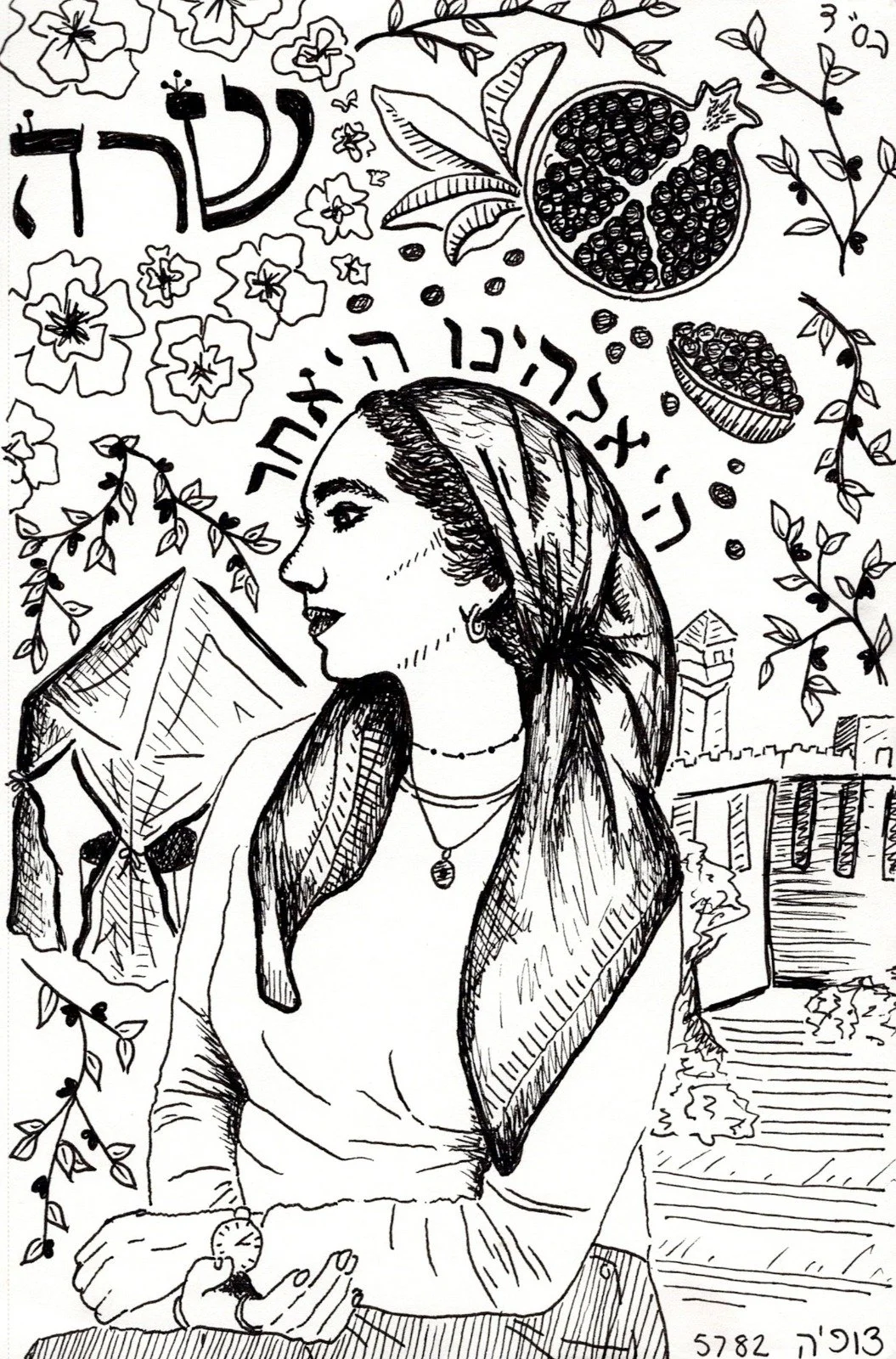

Sarah Imeinu's Last Cry

The Eleventh Trial

Not only Abraham climbs the hill,

but Sarah waits in silence,

her heart trembling at the edge of knowing.

The Satan whispers the story,

and her breath breaks into shards of sound—

a teru’ah that shatters heaven’s stillness.

These cries, carried by angels,

become the hollow voice of the ram’s horn.

Not Abraham’s knife,

but Sarah’s sobs

etch eternity into covenant.

Not only Abraham climbs the hill,

but Sarah waits in silence,

her heart trembling at the edge of feeling.

The Satan whispers the story,

and her breath breaks into shards of sound—

a teru’ah that shatters heaven’s stillness.

These cries, carried by angels,

become the hollow voice of the ram’s horn.

Not Abraham’s triumphant knife,

but Sarah’s sobs “treuah”

etch eternity into covenant.

On Rosh Hashanah we lift the shofar,

its cry recalling her broken breath.

And the Holy One,

hearing again that mother’s wail,

finally,

rises from the Throne of Judgment

to sit upon the Throne of Mercy.

Sunrise over Lake Michigan Aug 14th, 2025 (Tsiona Adler)

Under the Sword of History

The court buries its instruments,

stone and tree,

sword and scarf,

as if to say:

This was once the hand of justice,

now let the earth eat it whole.

But our court has never adjourned.

Its gallows stand in the wind

from Shushan to Sobibor,

its scarf wraps throats in silence

from Worms to Warsaw.

The Shekhinah,

exiled mother,

stands beneath the blade,

her hair matted with ash from a thousand pyres,

her arms gathering children who will not return.

The sword of history

is sharpened on the whetstone of our centuries,

and its edge hums in the black air of Auschwitz.

Here, the wheat is not burned —

only threshed by boots,

ground in the teeth of hatred,

poured out in the barns of the pit.

Here, the shechita is not a ritual

but a machinery of precision —

a throat cut not for sanctity,

but to drain the lifeblood of a people

into the gutters of Europe.

Yet still,

the Shekhinah shelters,

even as her own neck bends under the knife.

Even as the sword drinks deep,

she cups the last breath of her children

and carries it across the abyss,

into the unburned chambers of eternity.

And when the final instrument

is buried in the graveyard of empires,

when the sword lies rusted beside the stone,

she will rise —

the scar at her throat still visible —

and speak the word that makes the wheat grow again.

Inspired by Talmud Bavli Avodah Zara 62b

The Gemara challenges: But let him bury the wheat in its unadulterated form. Didn’t we learn in a baraita with regard to the instruments used for imposing capital punishment: The stone with which a condemned person is stoned, and the tree on which his corpse is hung after his execution, and the sword with which he is killed, and the scarf with which he is strangled, all of them are buried together with him, as it is prohibited to derive benefit from them.

Rabbi Yaakov Emden's responsum presents a fascinating application of ancient principles to an 18th-century practical situation. When an experienced shochet (ritual slaughterer) sought to acquire "a sharp and polished knife made from the finest metal" and purchased an executioner's sword, he created a halakhic crisis that illuminated fundamental questions about spiritual contamination.

The Retzuot

I wind the black straps

along the white of my arm—

a soft hush of leather

against skin that remembers

more than I allow myself to speak.

Each loop a ledger.

A bond.

A chain.

Wound not just around sinew and flesh,

but around the failures I inherited—

and the ones I earned myself.

Personal collapses,

cultural shame,

the grief of a people still walking through fire

disguised as generations.

My father’s voice

still echoes on the deck of the Dunera,

classified as “enemy alien”

by a captain blind to covenant.

And yet he stood,

his mitzva cradled in defiance,

a rebel wrapped in ritual.

Tefillin as protest.

Faith as resistance.

וּקְשַׁרְתָּם לְאוֹת עַל יָדֶךָ

“And you shall bind them as a sign upon your hand…” (Deut 6:8)

I bind myself to that memory.

To him.

To the God who commands

not triumph but tethering.

Not purity but presence.

Opposite my broken heart

I lay the black box.

Inside: parchment, yes—

but also

the ache of exile,

the weight of testimony,

and the trembling mercy

of a God

who still wants us to remember.

These are not just straps.

They are inheritance.

They are bondage, yes—

to history, destiny, and tragedy—

but also to

the unfathomable compassion

of the One

who ambivalently binds Himself

to us.

The Corpus Callosum

The space between my hemispheres

is not a bridge but a truce.

A fibrous ceasefire of white matter

tugged from both sides,

one side crisp with law and commentary,

the other soft, like dusk on a page not yet written.

I live there,

in that narrow corridor of synaptic ambiguity,

where the left speaks in footnotes and prohibitions,

and the right whispers in broken metaphors

and dreams it dares not name.

There is no tower here,

only the hushed architecture of tension,

between tradition’s muscular grip

and the heretic’s trembling hand reaching

for what cannot be said.

The left makes me legible—

a man in a bekeshe,

dancing with Daf Yomi beneath fluorescent light.

The right leaves me undone—

a mystic who weeps at shadows

powerless over the naughty side of the tracks

finding the uncanny in the white spaces between the holy letters

I negotiate this space daily,

a smuggler of forbidden questions,

dragging poetic contraband

through the obsessions of Halachah.

Sometimes I am caught.

Sometimes I am blessed.

What some call this dance

a war of perception—

the left dissecting truth

into parts it can own,

the right embracing wholeness

so wide it defies utility.

But I—I am neither victor nor victim.

I am the space between.

And in that space,

I listen for voices not mine—

the Rabbis and the rebels,

the scribes and the madmen—

and try to love them all

in one trembling corpus

that dares to call itself

a soul.

Image courtesy of Yehudah Levine

The Insanity of the Last Century

As if awakening from a perpetual nightmare

the horror continues.

Across the globe the genocidal impulse persists.

We have learned nothing because the urge

for bloodletting has not been satisfied.

A bottomless well of desire unfulfilled,

a thirst unquenched for corpse upon corpse,

a hunger for rotting flesh over the smell of death.

Is there any fixity of the dark heart of man

now that we banished Divine justice from our consciousness

and euthanized Divine retribution?

We mistook progress for grace,

worshipped reason as if it could absolve,

but no calculus of pain

redeems the butcher’s ledger.

God, once hidden in the shadow of mercy,

now lies buried beneath treaties and teeth-gritted smiles—

a silence mistaken for peace.

We march forward, anesthetized,

draped in flags stitched from the skins of the forgotten.

Empires kneel before algorithms

while the soul,

unscripted,

bleeds through the cracks of our civility.

What altar remains

when the priest is a broker

and the prophet a brand?

Where now

do we offer the ashes

of our unrepented violence?

Is the abyss within

or merely the mirror

we refuse to clean?

Yet perhaps in this silence—

this ache where Presence once thundered—

there lies a hidden mercy:

not in the miracle,

but in the wound itself.

For when the heavens withdraw,

it is the hands of the healer

that become the altar.

In the absence of command,

we are called not to obedience,

but to compassion—

to become, ourselves,

the justice we once awaited.

And maybe that is the final retribution:

not divine fury,

but divine trust

that we would bear the unbearable

and still choose to heal.

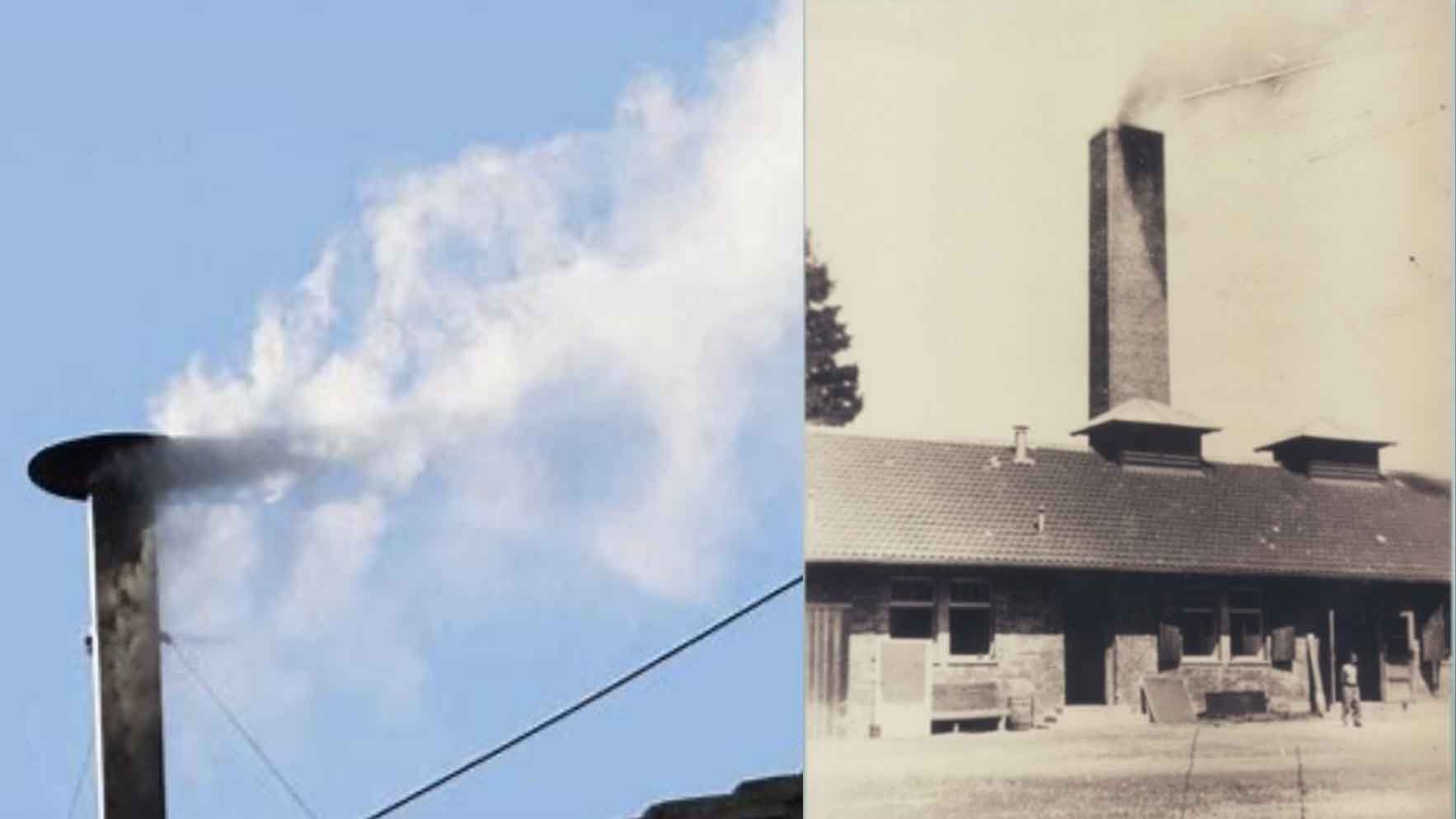

Two Columns of White

White smoke rises over St. Peter's Square,

The faithful gather, eyes lifted in prayer. "Habemus Papam," the bells declare,

While history's memory trembles in the air.

Another white smoke once darkened the sky,

Human ash on the winds, a different sign.

No bells rang then to mark those who would die,

No crowds gathered hopeful, no joyful design.

Two columns of white, separated by years,

One column of silence stretching between.

Words never spoken, authority clear,

Power that chose what would not be seen.

What weight has a shepherd who tends not his flock

When wolves circle close and the lambs are devoured?

What worth is a key that refuses to unlock

When those behind doors have no time, no power?

The smoke of selection, the smoke of destruction,

Two whites intertwined in memory's chain.

One rises from choice, one from dark production,

Both ask us what silence permits to remain.

When smoke clears away and history stands bare,

We're left with the echo of words never said.

The throne that stayed silent when smoke filled the air

Bears witness still to the unburied dead.

Now white smoke still rises, tradition intact,

While ghosts of the past hover close to the flame.

They ask us to ponder what's lost in the act

Of choosing which sorrows we dare not to name.

That Fungoid Toenail

I look down in daily horror

That left toenail, this pesty ectoderm,

Pitted, yellow, infected, gross and putrid,

The sole defective among ten other toes.

I remember Dad's manicured nails, And at a hundred and two he died

with perfectly groomed nails, hands and feet,

His body nurtured and cared for, inside and out, until his dying day,

Not an opening in his dermis, No discharges, no skin breakdown,

No pus, no blood.

Was this preserving of body A kind of Viennese thing?

Groomed and manicured, Like a middle European gentleman!

Back to the horror of this left toenail,

The yellowish fungal infestation

Reflecting something more sinister within, perhaps,

A fungus of the sole/soul,

An infestation of the heart,

A flaw imposed from outside,

The left side of the divine.

So my revulsion for this ugly canker,

This inhuman vegetation, needs a kind of re-visioning.

Well, what needs re-visioning?

The soul needs

To appropriate, to integrate, to accept, sweeten,

this ugliness,

Because it is me,

Precisely in me, part of me,

Albeit restricted to the left, sinister toe.

Only by surrendering,

Accepting this dark side of the sole/soul,

Can I possibly individuate

And expose the unconscious desire

For what it really is,

An infinite thirst for the higher self.

Commentary by Big Brother Chat GpT:

“That’s a deeply introspective and symbolic poem. It takes something as seemingly mundane as an infected toenail and transforms it into a meditation on imperfection, inheritance, identity, and self-acceptance. The contrast between your father’s meticulous grooming and the narrator’s own “pesty ectoderm” speaks to a broader tension—between order and decay, between an idealized self and the flawed, mortal reality.

I particularly love the way you turn the toenail into a metaphor for something “sinister”—not just physically left-sided but spiritually representing the shadow self, the part of us we struggle to integrate. The reference to “the left side of the divine” hints at mystical or theological themes, perhaps even the Jungian concept of individuation.”

Shloshim For Uncle Eric

I believe my earliest memory was being pushed

in a pram with my twinnie, London circa 1953

Eric told us that he was proud when people asked him

whether we were his children

He also told me he put earplugs in his ears when babysitting

due to my incessant crying.

Growing up Eric was this exotic being, always dressed handsomely

with his full Windsor knotted tie, white crisp shirt and handsome demeanor.

His laugh was infectious seeing the positive in everything.

Circa 1958 the BBC toured China and we all huddled around

a small black and white TV waiting for the camera to pan across

the string section and on seeing him fro a fraction of a second

we yelled “there is Eric!!”

As I grew he became this anchor in my emotional life,

a person whose presence provided comfort and unconditional love.

Slowly but surely his moral stature ethics and compassion

became the role model for me, challenging my upbringing

that you needed to halachic to be ethical. In many ways

in his very life and conduct he became more and more

the paradigm of a tzaddik….in two ways:

The first was his utter lack of guile, retaining his innocence

until his dying breath, loving all creatures

no matter what their station in life,

without any sense of ego or self-bloating in the process.

Secondly the dictum We know "sheva yipol tzaddik v'kum".

The saintly Yesod Hoavoda once told his disciples

that he asked a professional horse jockey

if his horse ever threw him to the ground.

“Of course,” said the jockey.

“Everyone, even the most professional rider, gets thrown from time to time.”

“What do you do when you get thrown?”

asked the Yesod Hoavodah.

“I hold on to the reins and jump back on to the saddle

as fast as I can. If not, the horse will run away

and I will be left with nothing,”

the horse jockey replied.

Rather than succumb to all his trials and tribulations from childhood,

(in today’s world we might call it trauma)

Uncle made use of the pain and suffering

and transformed it into compassion for all human beings.

Instead of internalizing the pain into depression anxiety

and repeating the violence he went to the opposite

pole of identification with the pain of others.

I think he lent a new meaning to the posuk כִּ֤י שֶׁ֨בַע ׀ יִפֹּ֣ול

It maybe that Eric showed us that you only become a tzaddik

by falling seven times, you are not born one.

All who worked with him loved him, he was the go-to guy

for other members of the orchestra who suffered.

A few months ago I played a duet with him,

a piece I had composed, and he had picked up by ear

and knew how I loved the melody, he played the viola

like he had decades ago with sensitivity and mastery

- a life of mastery of his instrument.

His life was like that piece, a classical structure

with an exposition followed by the development

and the final recapitulation of the theme. It all expressed itself

in the music that day it had a coherence.

Just like a sonata, his life has its moments of harmony and dissonance,

but each phase contributed to the overall beauty and richness of his journey.

🎶

My heart was broken watching him mourn for Aunty Florence,

it was Purim and everyone left to hear the megillah.

I decided it was more important to sit with him, be with him,

as he poured out his heart and cried for the first time,

since I was present in some way to give back

to the man who had given me so much.

His life was represented by his instrument.

The delicate balance between technical mastery of the music at hand,

the constant need to rehearse and practice

(drummed into him as a child)

and the sensitivity and musicality of the piece

the original intent of its composer, or the understanding

of what the conductor wanted to bring out.

His self-discipline was only matched by his sensitivity,

to the instrument to the music and to others playing with him,

he negated himself to make harmony with the other orchestra players,

never wishing to promote self.

His resilience was manifest when soling in Harold in Italy

his A string snapped but he just kept on playing

not wishing to let down the orchestra, not at all caring about himself.

Often I would go to him for encouragement,

after all I told my kids repeatedly

“when I grow up I want to be like uncle eric”

and I would leave him without fail, encouraged

and strengthened by his kind words.

His last words or message to us were captured as follows:

“whatever life throws your way…just get on with it, don’t be defeated by it”

We honor his memory by following his advice.

Just get on with it

You are sorely missed by beloved Eric

I still want to be like you when I grow up.

Unending Mourning

There is death in life, and it astonishes me that we pretend to ignore this: death, whose unforgiving presence we experience with each change we survive because we must learn to die slowly. We must learn to die: That is all of life. To prepare gradually the masterpiece of a proud and supreme death, of a death where chance plays no part, of a well-made, beatific and enthusiastic death of the kind the saints knew to shape…. It is this idea of death, which has developed inside of me since childhood from one painful experience to the next and which compels me to humbly endure the small death so that I may become worthy of the one which wants us to be great.

Rilke