For the source text click/tap here: Zevachim 38

To download, click/tap here: PDF

Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel argue about how many blood applications are necessary for a sin offering. All agree that four applications are required, but Beit Shammai say that the offering is already valid after two such applications, while Beit Hillel maintain that even one is sufficient.

Beit Shammai rely on the phrase "on the horns" repeated three times. Since the minimum of the plural "horns" is two, altogether this counts as six. Four of these six teach the prescribed procedure, and the remaining two tell how many are absolutely necessary. Beit Shammai rely on the pronounced form of the word "horns".

The scriptural basis for the dispute lies in Leviticus chapter 4, which prescribes the ritual procedures for various categories of sin offerings. In verses 25, 30, and 34, the text commands that the priest shall take the blood of the sin offering and place it "on the horns of the altar" (Hebrew: קַרְנֹת הַמִּזְבֵּחַ, karnot ha-mizbeach).

Beit Hillel point out that the written form for two of the three "horns" can be read as "one horn". Beit Hillel attach more importance to the written form of the word. This gives them four "horns", three for the prescribed after the first application, and one that is necessary for atonement. But Beit Hillel's count is inconsistent, they should use all four for the prescribed application, with none necessary to achieve atonement! They answer that we don't nowhere do we find atonement for nothing.

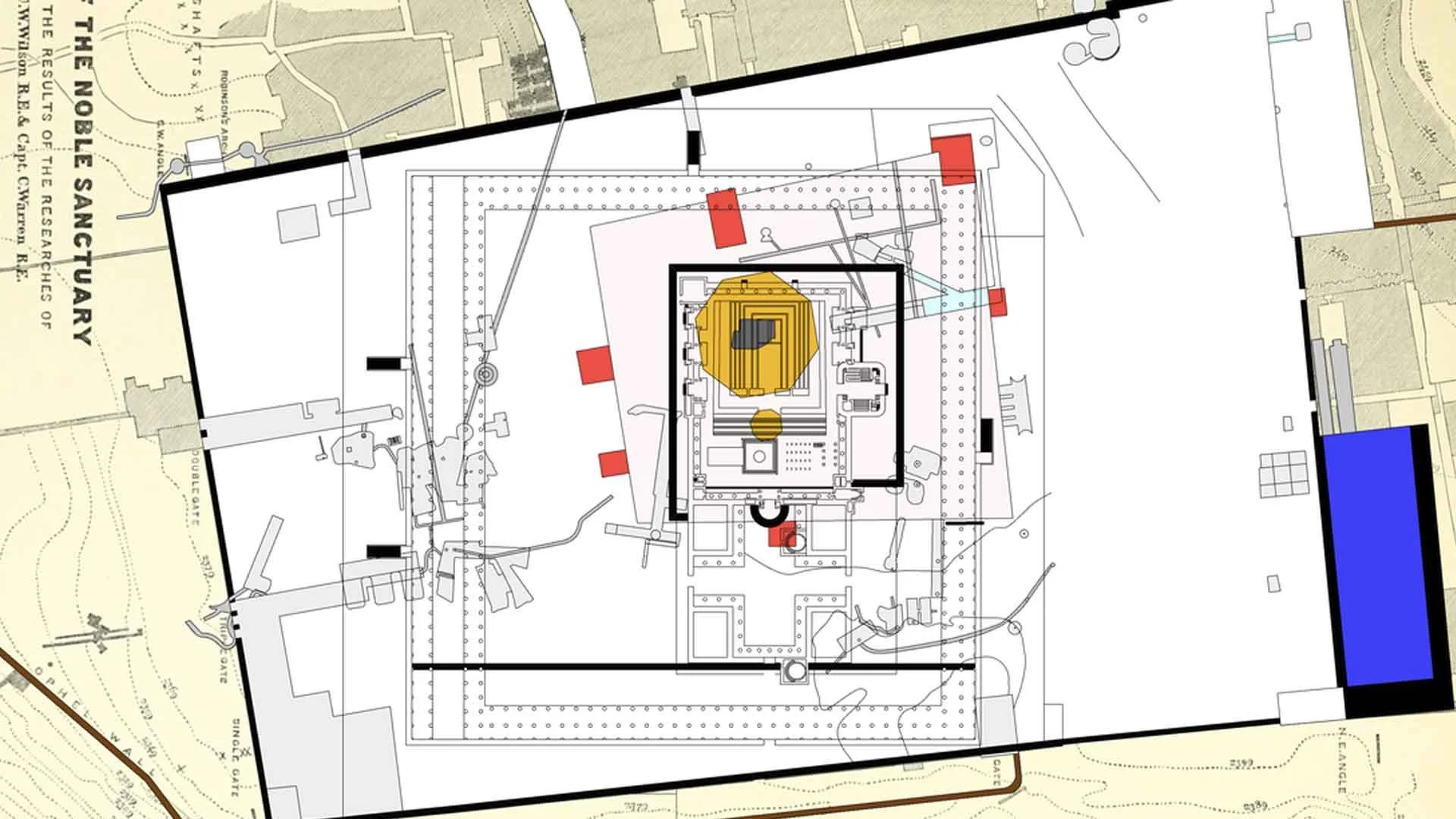

The interpretive challenge arises from both the repetition of this phrase across three verses and the grammatical form of the word "horns." Baruch Levine notes in his commentary on Leviticus that ancient Near Eastern altars typically featured four elevated corners or "horns," which held particular religious significance as points of sacred contact.

Archaeological evidence from various sites confirms this four-horned structure as standard for Israelite altars.